HUMOROUS

When I was 12, two neighbor boys, both a couple of years older than me, got the bright idea we should go hunting for squirrels in the woods above Skyline between Piedmont Avenue and 40th. John Durfee, one of the kids, didn’t have access to a gun but Ricky Plys, the other kid, did. A .22. But Ricky’s dad had locked up all the ammunition. So, we had a gun, but no bullets. I solved the problem by digging into my dad’s closet and liberating a box of .22 long rifle rounds. Off we went.

After plinking at stuff for a couple of hours, we decided it was time to head home. John led the way and I walked behind him. Ricky followed with the .22. Somewhere on the trail, my gun safety training kicked in. I’m not supposed to be walking in front of the kid with the gun, I thought. I peeled off and walked behind Ricky. But Durfee was still ahead of Ricky and the .22. Somehow, Ricky stumbled, the gun went off, and a bullet hit John Durfee in his leg and traveled up into his back, near his spine. Ricky’s response? He took off, leaving the smallest kid behind to try and help the biggest kid make it home. As we limped along, John came up with a story. His dad, who was a hunting buddy of Harry’s, was the Chief Public Defender. Represented some nasty dudes in serious cases. “Here’s what we’ll tell ‘em,” John said between bouts of crying and pain. “Some guys were across the valley, on the ridge. One of them said, ‘Hey, isn’t that Durfee’s kid?’ The other said, “That’s him, alright. Let’s get ‘em.’ They shot me and took off.” Durfee looked at me, his eyes defiant. “Got that?”

So, when I managed to drag John into his living room, where his dad, a seasoned trial lawyer interrogated us, that’s the story we told. Before Jack could rattle me, I skedaddled up the hill. My house was only a ½ block away. And I had a problem to be rid of: I still had a bandolier of .22 rounds tucked inside my sweatshirt. Between when I left Durfee’s and stopped at my shack, opened the door, and tossed the bandolier inside, Jack smelled a rat and called Harry. I didn’t know it but my dad was standing in the picture window of our house, phone in hand, getting the low down from Jack, while watching me hide evidence.

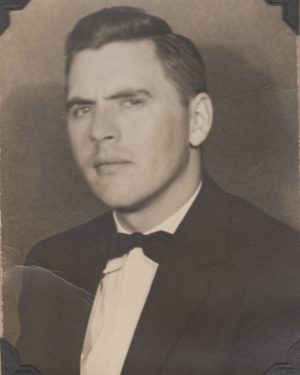

I came in the back door and there was Harry. Dad was, when his dander was up, a very scary guy. I took one look at his face and I knew he knew.

“What were you doing?”

“Nothing.”

“Where have you been?’

“Nowhere.”

“What did you throw in your shack?”

“I wasn’t at the…”

I never finished the lie. Harry had me by an ear, out the door, across the lawn, and standing next to the shack in mere seconds.

“Get it”, he said.

Dad was silent during the walk to Durfee’s, but held my neck in a firm grip. The ambulance, its red lights flashing, its siren blaring, was just pulling away from the Durfee house when we stopped in front of Jack and two cops.

“Boy’s got somethin’ to say…” Harry said, shoving me towards The Law.

They found Ricky Plys hiding under his bed with the .22. The cops put the two of us in handcuffs, drove us downtown, fingerprinted us, interrogated us, and scared the shit out of us at the request of Jack Durfee and Harry Munger. I won’t say I never strayed after that. I can say I was never again a guest in the back of a squad car.

My sister Annie recently made this observation: Our dad was a tough, ornery, cranky, opinionated son of a gun who came down hard on us when we messed up. But just as quickly, he had the ability to move on without ever throwing our sins back in our faces. He never dwelled on history when it came to our missteps. In the fifty-three years since John Durfee got shot, Harry Munger never once told that story.

TOUCHING

If you know the Mungers, you know that there are times when one Munger refuses to speak to another of the clan. Such impasses occurred between Dad and me over the years. The reasons behind these silences aren’t important, never were. They just happened. But during the last six months or so, Harry and I didn’t have any spats. Our truce, such as it was, saw us calling each other 2-3 times a week. He loved it when, during this past winter, I repeatedly bemoaned that it was below zero or snowing, to which he would reply: “Well, it’s 85 and sunny here and I just got out of the pool.”

Mom and I have always said, “I love you” to each other. Not so Harry and I. We’re guys. We just don’t do that. An occasional hug, sure. A firm handshake? Always. A kiss or an “I love you”; not in the cards. So when, over the past five or six years, Harry began ending our long distance phone calls with, “I love you,” it caught me off guard. Something had changed in him, making him more sentimental, more affectionate. He never hung up the phone without saying, “I love you, Son.” That phrase, quite frankly, was rarely reciprocated. It just wasn’t in my wheelhouse to repeat those words to my old man. I did on occasion. But those occasions were few and far between.

Friday, April 27th. I called Harry. We had a nice talk. He’d just come from the pool. He didn’t tell me, as Pauline later revealed, that he’d been unusually tired, having slept nearly 20 hours before making his way to the pool. In any event, Dad and I came to a logical place to end our conversation. There was a second or two of silence. Before he could say anything, driven by whatever foresight or grace or intuition was granted me, I said, “I love you, Dad,” and I hung up the phone.

I said those words because Harry had brought about a positive change in our relationship. It was the last time we spoke. And it was a gift.

Thank you, Dad.