I read with some interest a recent letter to the editor concerning my alma mater, Duluth Denfeld High School. The writer seemed to advocate returning Denfeld to its “roots” as a training ground for the trades, back to a Smith-Hughes-style curriculum to re-emphasize blue-collar trades and de-emphasize careers in education, the law, engineering, medicine, or other professions. As I write this response, it’s no secret that parents and educators and administrators and school board members are discussing ways to restore population and opportunity equity between Duluth’s two public high schools. I have no skin in that game. All my children went to Hermantown schools. My wife Rene’ and I made a choice 34 years ago to live in the country, a choice that had nothing to do with the Duluth school system and everything to do with lifestyle. We didn’t leave St. Marie Street in Duluth because of educational turmoil. But it seems given the recent, passionate debate concerning the disparities between Denfeld and East, some Duluth parents might be making choices for their kids based upon the lack of opportunities available for kids living on the Hillside and out West. If that’s the case, I think calls for changing Denfeld’s educational mission and focus would be a serious mistake.

I was never the smartest kid at Piedmont, Lincoln, or Denfeld. But Gary Ames (my 4th grade teacher) apparently saw something in me. My perceived abilities were limited to reading, writing, English, and the social sciences. Though I took accelerated science classes later in my public school education, my math skills remain rudimentary. No calculus for this guy! But thanks to Mr. Ames, I spent an hour a day in 4th grade concentrating on reading and writing with Mrs. Zakula. Because of my participation in Mrs. Zakula’s workshop, I found myself plucked from Mr. Child’s sixth grade class at Piedmont to spend mornings at Lincoln Elementary with kids from Stowe, Morgan Park, Riverside, Irving, Laura MaCarthur, Merritt, Bryant, Ensign, and Lincoln: elementary schools located in the Western half of the city. Two kids were named from each school to spend time with Miss Hollingsworth; a dedicated, smart, no-nonsense teacher who tried to keep twenty or so gifted students engaged. My partner in crime from Piedmont was Jan Erickson (now Larson). Our moms took turns driving us to and from Lincoln. We’d work on English, writing, spelling, reading, drama, and history/geography at Lincoln, eat our lunch, and then head back up the hill for math, science, art, and gym at Piedmont. We weren’t teased or ostracized or ridiculed by our Piedmont classmates. It was an accepted part of the day that Jan and I would wander back after lunch and resume our seats at Piedmont for the afternoon session. And the kids who spent time with Miss Hollingsworth? What became of them, these children of ironworkers and steel plant employees and electricians and custodians and nurses and railroaders? You already know my story. Jan became a pharmacist. Other “special” class members became engineers, professors, chemists, teachers, and school administrators. Some, its true, migrated towards blue-collar jobs, working in construction and the mines and the like. But so far as I know, all went on to lead productive, enlightened, engaging adult lives.

Personally, I carried with me a singular skill from my time with Miss Hollingsworth, a skill that served me well throughout junior high, high school, college, and law school. One of the most important components of mornings spent under Miss Hollingsworth’s tutelage was the requirement that we write, edit, and compile three massive written reports during the year. One had to be a biography. One had to be a historical and geographical review of a foreign country. And the third? We were allowed to choose any topic we wanted to write about. In addition to meeting certain size, illustration, and editorial limitations set by Miss Hollingsworth, we were also required to give an oral presentation of our reports to the class. The fact that Miss Hollingsworth required us to produce documents that, quite frankly, went beyond any writing assignment I encountered until college, and then get up and talk about our work, well, that experience alone was enough to ensure we were successful as we entered adulthood and went off to college, the trades, or the military.

The bottom line is, had Mr. Ames or Mrs. Zakula or Miss Hollingsworth not seen something in this Piedmont kid, or if the other teachers in all those other Western elementary schools not seen similar attributes in their students, who knows where we would have ended up in life. There’s certainly no shame in being an electrician, a welder, a bank teller, or a caregiver in an assisted living facility. All trades, jobs, and professions have their own sense of duty and honor and dignity attached to them. But to suggest, as the recent letter writer did, that kids from the Hillside and the Western half of Duluth should somehow be limited in their aspirations seems to me to be shortsighted and ignores the history of what kids from those neighborhoods are capable of achieving.

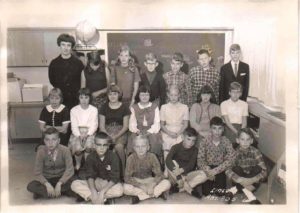

( (c) Mark Munger 2017. This essay originally appeared in the Duluth News Tribune. Mark is the young fella, fourth from the left in the first row. Ms. Erickson Larson is in the middle row, second from the left.)