Two hours passed. The fog closed back in again making it safe to walk or sit aboveground. Kids talked, whittled, and dug elaborate shelves and steps in their holes. Several went down and helped Gambaccini and Jacobs dig graves for the dead NVA, simply for something to do. Many dozed, thankful to have nothing to do but wait in their holes. All of them looked at the sky every few minutes, like cultists waiting for deliverance. Two and a half more hours passed. Mellas crawled down to check on Goodwin. Goodwin was still waiting over his rifle. Mellas lay down beside him. Goodwin talked without taking his eye from the rear sight. “That little bastard’s just about to poke his head out that hole. I can feel it.”

(c) 2010, Karl Marlantes.

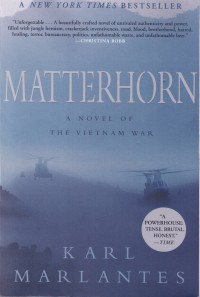

Matterhorn; A Novel of the Viet Nam War by Karl Marlantes (2010. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-4531-4)

The novel as therapy to heal. Once you have finished this mammoth work of fiction, which, in many ways, is the quintessential novel of the Marine experience in the Vietnam War, you realize that’s exactly what this book is: Therapy. We sent hundreds of thousands of our boys (and a few thousand girls in supporting roles) to fight in a war that made, in the end, absolutely no political, military, or strategic sense. Marlantes captures the larger frustrations about the Vietnam conflict after Nixon’s election in 1968 in the minutia: The day to day experience of Lieutenant Second Class Mellas, an Ivy League educated Marine Reserve Officer who has, unlike so many of the men drafted to fight and suffer, volunteered for his role. This is likely the grittiest, most realistic war novel ever written. One jacket blurb compares Matterhorn to All Quiet on the Western Front. That’s a comparison that hits the mark: Both the so-called Great War (WWI) and Vietnam share a certain political insanity, a sense of helplessness in the face of governmental decision-making, that is best depicted in the day-to-day terror confronting the line soldiers in the two stories.

The writing is crisp, raw, and real: Like finding a bevy of leeches sucking blood from your leg under your utility trousers in a shallow trench while you try to sleep; or shitting blood and water as you shiver in the cold mountain air of what is supposed to be a semi-tropical country waiting for a medal-crazed colonel to order you to re-take a hill that, a week earlier, that same colonel abandoned as having no strategic importance. There are a few scenes that drag (generally those away from combat, where the interactions between members of Bravo Company become more personal, more detailed). Some of this less harried dialogue is necessary to form character: some of it is simply extraneous. But the overall quality of the book is superb and, once you grasp Marlantes’s brilliance as a chronicler of war, you will forgive these minor lapses. Not since Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried took the reading nation by storm has a novel of Vietnam hit such a high and consistent note. On film, though I’m a fan of Platoon and The Deer Hunter, about the only movie that approaches the emotional content and the combat realism of Matterhorn is Mel Gibson’s terrifically underrated When We were Soldiers. Read this novel and then watch the movie and you’ll understand what I mean.

There are no straw men, no men of pure evil or pure virtue in this book. Marlantes has captured the nuances involved in depicting humanity at war with boldness. He also does not shy away from the complex politics or issues of race and economic status that, to this day, remain as questions regarding who goes to war for America and why they are sent. The racially charged scenes, the tension, and the results of the exchanges between Marines of black and white skin, are honestly and thoroughly examined. I remember being told in Platoon Leadership Class (PLC) at the Marine base in Quantico, Virginia, that “there is no color in the Marines but green”. Marlantes unveils the truth behind that myth by his depiction of the tensions percolating beneath the surface in the American military during the heady days of the Civil Rights Movement where men of disparate skin color eyed each other warily over the sights of their M-16s. Again, it is an open, honest, and, hopefully for Marlantes and other veterans of that godforsaken war, cathartic telling of the truth.

A big book which, at its core, is a simple story of one man, one platoon, one company, and one battalion of the United States Marine Corps during the Vietnam War. Outstanding.

5 stars out of 5.