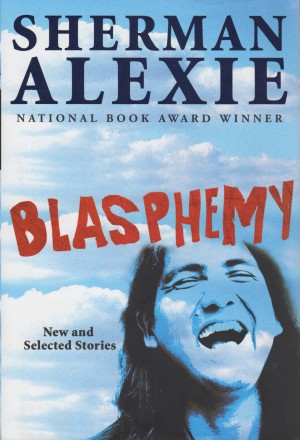

Blasphemy by Sherman Alexie (2012. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-2039-7)

Blasphemy by Sherman Alexie (2012. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-2039-7)

Ethnicity plays a role in most of my writing. From my first novel, The Legacy, which dealt with my maternal grandfather’s Slovenian roots in a historical context, to Esther’s Race, where I attempted to inhabit the skin of a twenty-something African American woman damaged by life, to my latest published work, Laman’s River, where I tackle the little known Mormon tenet of “the whitening of Native Americans” through intermarriage, I am always, it seems, subconsciously or deliberately writing about race, religion, and the differences between tribes of humanity. One of my favorite local authors, Linda Legarde Grover of Duluth, published a short story collection based upon her Native heritage entitled Dance Boots. Linda’s writing (you’ll find a review of the book in the archives section of this blog) has a mystical, lyrical quality to it, not unlike the voices one hears at indigenous drumming and dancing ceremonies. Well, after reading Sherman Alexie’s collection of short stories dedicated to and inspired by his own life as a Northwestern United States Indian (he uses the term throughout the collection as a term of self-description), I have to say: Alexi can flat out tell a story. Plain and simple. His style doesn’t avoid the mysticism and lyricism found in Grover’s prose but damps it down a bit and takes a different, albeit equal path, to perfection.

What do I mean? Let’s allow the author himself to show rather than having me tell. Here’s a passage from my favorite short story in Blasphemy, “The Search Engine”. By way of background, the female third person protagonist in the story is a university student enthralled with a little known Native poet. She finds a collection of his work in the college library, discovers she is the first person to check the book out since it was published in 1972, and begins a quest to find the author. The poet, a Native like the narrator, is a recluse, on the order of J.D. Salinger, though not nearly as famous. When the wide-eyed student and the old Indian finally meet up, he explains why he no longer writes:

He laughed. Corliss wondered how he could laugh. But she laughed with him and didn’t know why. What was so funny about the world? Everything! Corliss and Harlan laughed until the hearing-impaired bookstore owner felt the floor shake.

“So what are the lessons we can learn from this story?” Corliss asked.

“Never autograph books for drunk Indians,” he said.

“Never have sex with women named after celestial bodies.”

“Never self-publish your poetry.”

“Never perform at open-mike nights.”

“Never pretend to be an Indian when you’re not,” he said.

He took off his glasses and wiped tears from his eyes. Two Indians crying in the back of a used-book store. Indians are always crying, Corliss thought, but at least two Indians crying in an original venue…

“I never wrote another poem after that night,” Harlan said.”It seemed indecent.”

Alexie’s voice is heard throughout this lengthy collection, both in the first and third person, in male and female guises, beginning with youth and into old age. He tackles all the elements of contemporary Native experience with a deft touch, using humor, surprise, and introspection in equal doses. Some stories are lengthy, nearly novella like in scope. Others hardly fill a page, existing as mere snippets of postage stamp prose. But through all of the various voices and plots and characters, you will find nary a lapse in quality, nary a lapse in consistently magnificent writing. A National Book Award winner, this volume, like Grover’s Dance Boots (itself, a Flannery O’Connor Award Winner for Short Fiction), compels readers to consider a country within a country populated by tribes of indigenous people seldom discussed but always present.

5 stars out of 5. A book readers will devour and savor like wood-roasted venison.