Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation, so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

(Abraham Lincoln’s “Gettysburg Address”)

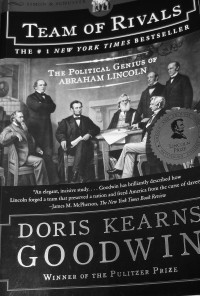

On Monday, I tried my best to honor Lincoln’s sentiment. I think I have a good handle on our 16th president, thanks to Doris Kearns Goodwin’s great book, A Team of Rivals, which I’m plowing through as my early summer read. So, with Lincoln as my guide, I pulled on a heavy jacket and drove into town to attend a Memorial Day remembrance at a local cemetery. I hadn’t been to a Memorial Day event in at least four years and felt it was my duty, my obligation to those who have served us and have given, as Lincoln so aptly described later in his short poetic speech, “the last full measure” for their country. Understand: My service in uniform was meager: I was in the United States Army Reserve during peacetime, saw no conflicts or bloodshed, and was never deployed overseas. About the only good thing that can be said about my service is that I received an Honorable Discharge for my efforts. So my compulsion to attend Monday’s service really was to honor others, folks who gave their lives to protect our democratic way of life.

The big white circus tent holding folding chairs, the stage, and the crowd quickly warmed with so many bodies (someone said over 500) crammed into the place. There was, as is to be expected, the Pledge of Allegiance to open the ceremony, followed by a spirited rendition of the “Star Spangled Banner” sung by a poised young woman with a great voice. And then came the invocation. That’s when, but a few moments into the event, I felt my heart drop. Not due to the weight of all of the departed we were there to consider, but due to the chaplain’s words. There, at a memorial service in honor of all who have served and given their lives, he did the inexplicable: He threw up an evangelical Christian prayer to the Almighty on behalf of the departed.

Now, understand, I am a Christian. Always have been, always will be. But I, like Lincoln and most of the great American leaders and thinkers who came before him have always understood this truth: Calling upon God in battle (or a football game, for that matter) to render your opponent impotent is a bit silly. There is very little of God in war. There is much of man. Perhaps, in a war such as World War II, or more recently, Bosnia and Afghanistan, where the evil of the opposition is clearly defined, invoking God as the arbiter of justice makes some sense. But in a war between brothers, Lincoln recognized that, as honorable as his move towards emancipation of the slaves might be seen, the Civil War was not fought, at its outset, to free a race but to preserve union. Invoking God in such circumstances; to, in essence, fulfill a political agenda, was not something our 16th president urged or contemplated.

Indeed, if you read the entire “Gettysburg Address”, you will note that Lincoln invoked the Creator’s name on one occasion, at the very end of the speech. Those who proclaim, as the chaplain seemed to be doing on the Memorial Day just past, that Jesus walks shoulder to shoulder with our military, in every conflict, on every battlefield, miss one very important point: Many of those who have died serving the United States of America in our armed forces, and who serve today, are not Christians. They are Buddhists and Muslims and Jews and Hindus and animists and agnostics and atheists. The very document that gives us our freedom to practice Christianity also protects the faith (or non-faith) of all men and women under arms.

Since the Revolutionary War, the armed services have tried to ensure that soldiers can practice their faiths, and that chaplains serve not only those of their own sect but all who may need pastoral care. The services have also sought to adhere to the First Amendment prohibition of any government “establishment of religion.” (Christian Science Monitor)

But things, on the most recent Memorial Day, took a turn for the worse. After a number of speakers, some additional music, and the introduction of the five WWII veterans who were on the stage, the master of ceremonies launched into, what, in my humble view, amounted to little more than an evangelical Christian sermon. There was no recognition in the address of the divergence of faiths and beliefs that has, since the dawning of America, been our hallmark as a country. And, as so many folks of a conservative religious bent are prone to do, the speaker emphasized a religious history of the founding fathers and our most beloved president, Abraham Lincoln, that is not buttressed by the record. Historian after historian has been quick to point out that Jefferson, Adams, Lincoln, Franklin, and Washington, and, two generations later, Abraham Lincoln, were men of tenuous faith. They were in no sense of the word, religious zealots and, in many ways, just like you and me, struggled with the fragility of their beliefs. Invoking their memories when offering up a wholly, and restrictively Christian theme to remember our fallen service men and women is not, in my humble view, accurate or appropriate.

When the event was over, I felt the opposite of what I had come to that big white tent to feel: Instead of being filled with patriotic spirit and reverence for those who paid the ultimate sacrifice, I felt betrayed, I felt used. Now, maybe it’s just me, the crazy Liberal seeker that I am. But I don’t think so. Unsure of myself, feeling that I had somehow lost my moral compass, I spent some time talking my feelings over with two men I respect: Wayne, a WWII fighter pilot and Roger, a Vietnam combat veteran. Both of them understood my point. Both of them, men who actually felt the breeze of bullets flying past them in war, agreed: To leave out those who are not Christians but who died in America’s wars is not what Abraham Lincoln envisioned when he stood on that platform before 9,000 Americans in 1864 and dedicated the Gettysburg cemetery.

My final thought, as I stood amongst the little American flags covering the cemetery grounds alongside the graves of veterans of our armed forces was this: How would Jack Litman feel?

You likely don’t know who Jack Litman is or was. Jack was raised on the Central Hillside of Duluth. He was also a lawyer and district court judge of some renown. Most folks who remember Jack, remember those details. But what many forget is that Jack was also a bomber pilot during WWII. He flew countless combat missions over Nazi Germany. That alone is enough to honor his memory. But here’s the thing that bothered me most about my experience on Monday: Jack Litman, a member of the Greatest Generation who was my mentor and friend, was a Jew.

Peace.

Mark

Mark, as an Evangelical Christian myself I have to agree with you. A Memorial Day speech should not be a platform to further ones religious agenda. I was a bit uncomfortable with the whole speech.Thank you for putting to words what I was thinking. God bless America!

Thanks, Don. I’m glad I wasn’t the only one. I’ll take the time someday soon to write the organizers and let them know my thoughts.

Mark