Day two. I wake after a hard sleep on a soft pad. I tug on my shorts, throw a shirt over my bare torso, clamp my Australian bush hat over my wild hair, pull hiking boots over bare feet, and stumble from the tent. After making the short trip to the Tettegouche Campground latrine, I fill pots with cold water and boil the water for coffee and oatmeal. My son hasn’t stirred despite all the noise I’m making.

Around the campground, other folks: couples and families, are stirring. Some are leaving their tents to take a morning shower. Others are revving up their $200,000 RVs for departure. But, despite all the humanity about the place, Tettegouche still holds plenty of appeal for someone like me, someone who enjoys the more primitive, the less refined. I clamber up a steep rock wall looming above our camp, a mug of freshly brewed instant coffee in hand, and sit on billion year old basalt looking out over the big lake, the Wisconsin shoreline a serpent to the east. There are no clouds in the sky and it promises to be a tough day to catch walleye on Tom Lake, our destination. Jack finally emerges from his sleeping bag (an unattractive butterfly if the bag is his cocoon): His hair is standing on end; his face is mushed from sleep; and his breath smells like roadkill. But, a cup of coffee, some hot oatmeal, a breakfast bar, a mug of Tang, and an apple later, followed by a trip to the shower ( and the application of a toothbrush) and my son is looking fine. After doing dishes, I too take my turn under the hot water of the camp shower. As I scrub away the dirt of our first day on the North Shore, I think back to how the state parks in Minnesota got hot water for their showers. Seems that the conservative members of the Minnesota House Natural Resources Committee chaired by my uncle Willard didn’t believe that campers needed such an extravagance. But Willard, like a good novelist, decided to show, rather than tell: He dragged a contingent of naysayers with him to the nearest park, spent the night in tents, and then, when the very tired and very hungry legislators were confronted by ice cold showers, he had his votes. (True story and you’ll find more like it in Mr. Environment: The Willard Munger Story. You can order a copy from the dashboard above. The book has been discounted to $15.00, $10.00 off the cover price!)

Once again, we’re early for check-in when we arrive at Judge Magney State Park north of Grand Marais.

“Hey,” I say to Jack.

“Ya.”

“Isn’t it a coincidence that a judge is staying at a park named for a judge.”

“Whatever.”

Apparently the irony isn’t as impactful as I thought.

Judge Magney State Park, a former WPA “Hobo Camp” from the 1930s, is smaller than Tettegouche but every bit as nice. We set up our tent, unroll our sleeping pads and bags, and head out to fish.

Tom Lake is windy. Jack isn’t happy when we unload the Grumman square stern, fire up the 2-horse Honda four-stroke, and begin crashing through waves.

“Let’s go back,” he whines.

“You’re kidding, right? It was an hour drive to get here.”

“I’m not fishing. Let’s go back.”

After raising three older boys, I know not to engage. I keep trolling, my nightcrawler and spinner deep in the cold waters of the lake. We work the shoreline. I catch two walleye the size of the chubs Jack caught on the trout stream. It’s too sunny for the fish to really be interested. After lunch in the boat and a couple more hours of trolling and drifting, we head back to the landing.

“That was a waste,” I complain as we hoist the canoe back on the luggage racks of the Pacifica.

“It’s a nice lake,” Jack says reflectively. “I’d fish it again on a cloudy day.”

Kid’s smarter than I am.

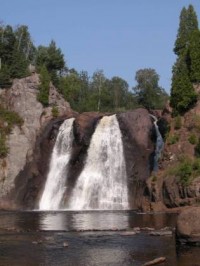

Back at Judge Magney, Jack convinces me we need to hike the Superior Hiking Trail and find a place to fish the Brule River. We hike for an hour and find our spot. As night settles over us, we work a deep pool beneath a small waterfall and finally, after two days of no trout, Jack lands a couple of nice ten inch rainbows standing in the thick mist coming off cascading water. He also manages to hook and land a large mouth bass, which, given that we’re fishing a North Shore trout stream, is completely unexpected. As I study the fish, trying to figure out why it is where it is, Jack becomes excited.

“You’ve got a fish on,” he says, noticing my rod dancing under my arm.

I release the bass and turn my attention to my fly rod. The tip of the rod is indeed twitching. I set the hook and know immediately that this is not a ten inch brook trout.

“Holy crap,” I say as the rod bends in half.

The fish dives and I give it line. After a few minutes of playing the fish, I work the it away from the rocks and ease it onto the shelf Jack is standing on.

“It’s a big bass,” my son says as the fish flops by his feet.

“No, it’s a brookie,” I correct my son. “And a damn nice one at that. Biggest one I’ve ever caught.”

Indeed. The trout is a beautiful 21″ coaster, likely a female getting ready for the fall spawning run. It is not a fish I want to keep.

“That is a big fish,” Jack says reverently.

“A legendary fish,” I reply as I pick it up. “Grab the camera.”

I try and hold the trout after releasing the hook from its hard palate but I cannot control the undulating mass of muscle and the brookie crashes to the rocky ground.

“Shit. I don’t want to hurt it. I want to put it back.”

I retrieve the fish. Jack aims the camera. The fish twists again and falls to the rocks.

“Shit. I do not want this fish to die.”

Eventually, after the photo is taken and after trying to revive the brookie in fast moving water, I give up: The fish is too far gone to release. I am not happy about keeping the fish and, had we been better prepared, I would have had a net handy. But it was a spur of the moment decision to follow Jack’s lead and fish the river. I lament the trout’s death but do not lament the excitement.

Thursday. We pack up camp and drive up the shoulders of the rolling Sawtooth’s into the interior of Cook County. Trout Lake is placid. There is no one else out fishing the tiny lake on this gorgeous Minnesota morning. We troll spinners and spoons and nightcrawlers in harnesses for brookies, lake trout, and rainbows. I have one strike. Other folks finally unload canoes and fish but all of us share the same bad luck. I have one strike but can’t hook the fish. And then, the blackflies, the curse of the Northland, find us. For the last hour of our time on the lake, as beautiful a little spot of sliver I’ve ever been on, the flies attack our bare ankles and shoulders mercilessly. No amount of DEET can dissuade the little buggers from landing and biting. We concede defeat and make for the landing.

On the way back down the hill towards the lake, we stop and spend the last couple hours of our trip on a tiny brook fishing for speckled trout. Intermittent clouds provide cover and we pull a few small brookies out of the unnamed stream. Jack finally has success and lands a half-dozen trout but keeps none. I keep one nice eight incher to go along with the big brookie from the Brule, which, when I gutted it, I discovered was a big male.

Still didn’t want to keep it. But at least it wasn’t a female full of eggs.

I bust out of the bush a good half-hour before Jack does. I sit atop a big steel culvert disecting the gravel road and eat lunch as I watch the creek course towards Lake Superior. No black flies or mosquitoes bother me and the warm sun feels good on my stubbly face. I pull out my tattered copy of Wisconsin and Minnesota Trout Streams by Humphrey and Shogren and read up on all the rivers, streams, and creeks waiting for an old man and his son to visit.

Peace.

Mark