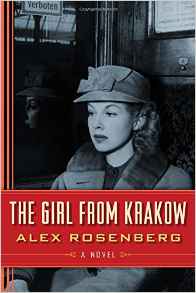

The Girl from Krakow by Alex Rosenberg (2015. Lake Union Publishing. ISBN 9781477830819)

I disagree with the reviewers of this new Holocaust novel who claim that Rosenberg’s story is bogged down by too many historical details, facts, and digressions. I agree with those reviewers who have written that they were disappointed that a man of Rosenberg’s education and intellect (professor of philosophy at Duke and author of numerous non-fiction books) allowed his passion for atheism, complex political theory, gratuitous sex, and endless speechifying disguised as dialogue to essentially ruin what should have been a monumentally satisfying story.

Like many of the readers who negatively critiqued the book (see Amazon and Goodreads for such discussions), I devour historical fiction. So when given the chance to download this new novel of Jewish loss and Nazi oppression for free on my Kindle, I did so immediately. I’m a fan of little known historical tidbits being turned into sweeping tales of heroism, loss, and redemption (which some claim I managed to accomplish in my three historical novels, The Legacy, Suomalaiset, and Sukulaiset). As one of my loyal readers, Davis Helberg says (paraphrasing here) “fiction can put meat on the bones of history.” And so, seeking to learn something while being entertained, I began my journey with Rita, Roseberg’s Aryan looking Jewish protagonist, with much anticipation. Unfortunately, the story never reached the heights of a true epic or the emotional depths of sorrow a novel set in WW II Poland depicting the ghettofication of Poland’s Jews should attain in the hands of a veteran storyteller.

There are simply too many coincidences, too many didactic speeches from the characters (think John Gault and you’re on the right track), and too much unplanned coitus (where Rita, at turns, beds her physician, manipulates a gay male friend to satisfaction, and spends months entwined in a lesbian relationship with the elusive and amoral Dani). Sure, I get that war, especially a war where you are compelled to wear a bright yellow star on your lapel, may reduce ethical considerations to memory. Lust, as the antidote for terror, or at least, a temporary release from constant threat of death, is a plausible reaction to the events depicted in this tale. Handled by a master narrator, such slides of morality might become plausible, even believable. But that’s not the case with Rosenberg’s somewhat clinical and methodical depiction of the various liaisons Rita entwines herself in.

Then too, there is the ending that seems highly implausible. All of this having been said, I did not, as some other readers of this new twist to an old story, stop reading the book. There was enough here to pique my interest (though maybe only of the male prurient variety) for me to finish the tale while bedded down in my tent at Hostfest in Minot, ND.Whether due to the fact that God is completely absent from the story (understandable since it is written from the viewpoint of God’s people being herded onto rail cars and brought to their deaths), or the author’s decision to cram political discourse into everyday conversation, or too many coincidences interrupting my suspension of disbelief, this effort left me without empathy for or emotional investment in the folks who survived the atrocities depicted. And that, I argue, isn’t of much value in a world already over-populated with skeptics and cynics.

3 stars out of 5.

Peace.

Mark