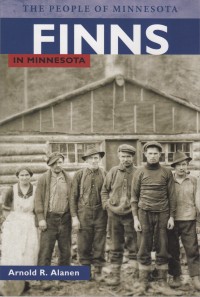

Finns in Minnesota by Arnold R. Alanen. (2012. Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-87351-854-3)

Anyone of Finnish descent interested in a brief, concise history of the Finnish experience in Minnesota should have a copy of this book on their shelf. Much more enjoyable reading than the leading text in this area of study (Hans Wasastjerna’s History of the Finns in Minnesota which has been out of print since the 1950s), Dr. Alanen does a credible job of distilling the statistics and anecdotes and historical references of Finnish immigration to the North Star State while providing just enough back story to make the migration pattern understandable.

As a non-Finn who loves writing historical fiction about these interesting and little-known people, I was struck by Dr. Alanen’s umbrage regarding the transliteration of lynching victim Olli Kiukkonen’s name into the better known moniker “Olli Kinkkonen”. The good professor writes, in speaking of the memorial stone placed on the unfortunate man’s grave by Finnish Americans (not, as Alanen asserts, in 1978, but in 1993 as noted in a piece on Minnesota Public Radio (see http://news.minnesota.publicradio.org/projects/2001/06/lynching/olli.shtml)) that “Kiukkonen’s surname was misspelled on his headstone.” One would suspect that the folks who placed the memorial (men and women such as former Finnish Honorary Consul Donald Wirtanen) knew which version of the decedent’s surname was appropriate for a headstone. In truth, which version of Kinkkonen’s name is used in retelling the tragedy, to this writer’s view, is less of a story than why he ended up dead.

Similarly, when writing about the politics of Finnish American radicals living in Minnesota during WW II, Alanen writes this about the outbreak of war between Finland and the Soviet Union in 1941:

In July 1941…the Soviet Union attacked Finland again, thereby initiating the “Continuation War”.

(p.66)

This passage seems phrased to leave readers with the impression that, upon conclusion of the Winter War in 1940, Finland’s government innocently went about its business until the Soviets launched another unprovoked attack on Finland in the summer of 1941. While it is technically correct that the Soviet Air Force began bombing Finnish cities on June 25, 1941 and that, up until that moment, no Finnish shells had been fired at the U.S.S.R., the truth is far more complex. For months prior to the Soviet air attack, Finland had allowed Nazi Germany to use Finland as a staging area for its air, land, and sea power as a prelude to the German invasion of the U.S.S.R. Indeed, there existed an agreement (between the Finns and the Germans) as to when and where Finland would attack the Soviets once operation Barbarossa, Hitler’s offensive against Stalin, began. This passage from Finland’s War of Choice by Henrik O. Lunde paints a vastly different picture of how and why the Soviet Union attacked Finland in 1941:

Finland declared neutrality when the Germans attacked the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. This official position was maintained until the evening of June 25 despite the fact that German aircraft began operations from Finnish airfields on June 23…The Russians retaliated with attacks on Pechenga, Kemijarvi, and Rovaniemi…The Finns later admitted that the presence of German forces in the country gave the Soviets compelling reasons for attacking.

(pp77-78)

Despite these minor inconsistencies, I found the book an enjoyable, quick read, and one the contains all of the essential historical, cultural, religious, and political lineage of the Finnish people who settled the various parts of Minnesota. I would recommend this slender volume as a starting point for any Finnish Minnesotan interested in his or her roots. I would also recommend that readers of Finnish extraction add “flesh to the bones” of history by reading my epic novel of Finnish immigration to northeastern Minnesota, Suomalaiset: People of the Marsh. (See above under the “Books” tab of the dashboard to order.)

4 stars out of 4.

Olli’s father’s family name was Kiukkonen, and his mother’s was Kinkkonen.

Olli was born in what was then Jaakkima, Viipuri, Finland. That place is located in the territory that the USSR took by force from Finland.

I’ve seen his surname spelled both ways in the newspaper accounts. I chose the “Kinkkonen” version because that was the one chosen for his grave marker by the Tyomies Society. Thanks for sharing!