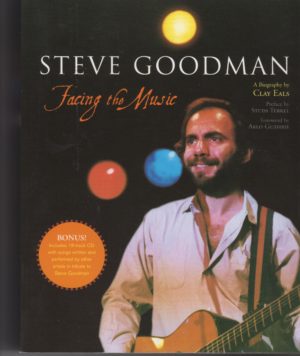

Facing the Music by Clay Eals (2006. ECW. ISBN 976-1-55022-732-1)

I want you to close your eyes. It’s 1977. You’re in a college ballroom on the campus of a medium-sized public university. The house lights are low. You are sitting on the floor cross-legged next to the girl you want to marry. There are maybe 100 other students and faculty sitting on the floor or in folding chairs arrayed in a circle around a microphone stand. A short, slightly rotund, long-haired Jewish boy from Chicago steps from shadow into light and confidently plants himself in front of the microphone. An acoustic guitar hanging from a strap will remain unplayed throughout the first song. The singer, his brown eyes clear and bright, begins an a Capella lament:

Oh my name is Penny Evans and my age is twenty-one

A young widow in the war that’s being fought in Viet Nam

And I have two infant daughters and I do the best I can

Now they say the war is over, but I think it’s just begun.

If you can visualize the scene and hear Goodman’s voice, then you will understand how that concert remains, for me, along with seeing Bruce Springstreen perform live, on of the favorite musical moments of my life. “The Ballad of Penny Evans” was born of genius: a man singing in the voice of a war widow about the loss of her husband and what remains. And yet, unlike some other great songs written during the 1970s, it’s a song that very few folks know or appreciate. I’ve heard it performed publicly just twice in the thirty-three years since Goodman’s untimely death in 1984. Once in an Irish pub in St. Paul by a local dude simply making music and once, in my own voice, as I stood scared as a school girl in front of a live audience as the MC for Law Law Palooza at the Clyde Iron facility in Duluth raising money to provide free lawyers for the indigent. I’m pretty sure the dude in St. Paul hit the mark. Not so sure about me. But that’s the impact seeing Goodman one time, long ago, had on me. I bring all of this up as an introduction to my review of Clay Eals’s massive (778 page) biography of the singer/songwriter who wrote not only “Penny Evans” but some other very, very notable tunes, including “The City of New Orleans” (recorded by Arlo Guthrie, Johnny Cash, and Willie Nelson, to name a few), and “You Never Even Called Me by my Name” (a country hit for David Allen Coe). In between these well known songs, Steve Goodman penned such classics as “California Promises”, “The 20th Century is Almost Over”, and a host of others. But despite a great storyteller’s voice, mastery of the acoustic guitar, a wicked sense of humor, and a knack for creating memorable lyrics, Goodman never achieved universal acclaim. That’s the story Eals so painfully tells, along with Stevie’s 15 year-plus battle with leukemia, his roller-coaster marriage to Nancy, and his doting affection for his three young daughters. And, despite a misstep or two (sometimes bordering on redundancy) Eals manages to keep the life story of this beloved but obscure genius in focus throughout this massive read. The question I have to ask myself as I consider how to rate this book, how to fairly evaluate the over 1,000 interviews Eals conducted (with musical legends such as John Prine and Mary Stuart and Jackson Browne, and non-musical folks such as Hillary Clinton (who attended high school with Steve)) and mountains of newspaper and other written references that the author consulted to create a complete life of a man who died underappreciated by the general public, is this: Would anyone other than a devoted Steve Goodman fan or a Chicagoan want to read this tome? I think the answer is an unqualified “yes”. Here’s why.

First, Goodman was an Everyman, a Midwestern boy raised in a suburban, middle class neighborhood whose dad was a war veteran from the Greatest Generation, and whose Mom encouraged his career through its ups and downs, who, upon learning of his fatal cancer diagnosis just out of high school, was determined to “make it big”. He tried, like so many of us in the arts have, through sheer will of effort and personality and ability, to convince The Man (i.e., record company executives) and the public of his worth, wanting the brass ring so badly that, as Eals points out, he even moved his family to California in the misguided belief that being closer to the record producers would give him his “big break.” Instead, we learn that, as Steve’s studio career tanked (he was axed by both Buddah and Asylum), live audiences, from those who saw him on the “Austin City Limits” stage to fans attending over 200 Steve Martin concerts, loved him. Having only seen Goodman once, and having been enthralled with his story ever since, I can attest that, just like The Boss never leaves a stage without expending the last drop of sweat from his body, Steve Goodman was cut from the same cloth. When he performed live, he was “all in”. So it seems to me that anyone with any sort of unfulfilled aspiration, whether it be in music, writing, the arts, or some other endeavor, will appreciate the painstaking narrative created by the author to depict Goodman’s slender successes and luminous failures.

And then there is this: I’ve read many other memoirs and biographies of musicians, from Woody Guthrie to Neil Young to Dave Crosby to Springsteen and Clapton. I’ve found them all fascinating looks at how musicians find success, hit the wall at some point in their careers, and then recover. But none of those books tear back the curtain so we are there, in the moment, both on stage and in the offices of the record company executives making deals, like this compilation does. In addition, Eals takes great care to memorialize the songwriting process, both Goodman as a solitary bard scribbling away on his own, or during the collaborative chaos Goodman engaged in while penning masterpieces with John Prine, Mike Smith, Jimmy Buffet, and a host of others. The depth and complexity the author ascribes to the process of songwriting is something to behold and, by itself, makes this biography a worthy read.

In the end, the book is long-winded but beautifully written. The language is direct, concise, and never flowery or cumbersome. And, I sort of get why Eals wanted to include everything in this book. I did the same thing in my biography of my late uncle, State Rep. Willard Munger (Mr. Environment: The Willard Munger Story). I knew, as Eals did, that no one else was going to pen a biography of his subject, at least not one that would conclusively document the life of someone so iconic yet so underappreciated. And so, Eals, left in anything that was revealing about Goodman’s life and creative process. In the end, I think that’s a definite plus. The world can now understand the background, struggles, and brilliance of the man who wrote, what Johnny Cash once called, “The best damn train song ever written…”.

Singing Penny Evans.

4 and 1/2 stars out of 5. 5 stars if you are a Steve Goodman fan. It is a must read for you if you’re in that category!

Peace.

Mark