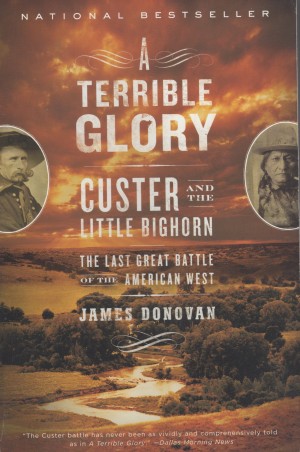

A Terrible Glory: Custer and the Little Bighorn by James Donovan (2008. Back Bay Books. ISBN 9780316067478)

I am a huge Custerofile (I made that word up). I visited the battlefield where Custer and over 250 of his troopers perished on June 25, 1876 as a young child, and having grown up in the era when television dramas were primarily exaggerated portraits of the old west (Gunsmoke, Maverick, Have Gun will Travel, Bonanza) or fictionalized tales of World War II, and being a kid prone to dreaming stories, the Little Bighorn loomed large in my youth. I’ve read just about every historical account of the battle placed in print and in fact, my historical research paper at UMD (my senior project) was an exploration of how the portrayal of Custer changed from fallen hero to scapegoat over the decades following the 7th Cavalry’s defeat at the hands of the Sioux and Cheyenne. My favorite account of the disaster (the word is loaded, I know; it wasn’t a disaster for the prevailing force of Native Americans protecting their way of life) is Son of the Morning Star by Evan S. Connell. Why? Because, I think, Connell managed to capture the story from both sides of the conflict, giving the legend of George Armstrong Custer a fresh and respectful analysis that included a reflection of what the Native Americans opposing General Terry’s expedition were grappling with as three columns of pony soldiers and infantry moved against men, women, and children of the Sioux and Cheyenne nations. I was hopeful that Donovan’s book, the latest in a series of investigations into the battle, would follow a similar path, perhaps adding nuance and detail that Connell’s work did not. But such is not the case.

There is precious little discussion of the Plains Wars from the perspective of the leaders of the various bands of Lakota, Dakota, Cheyenne, and other tribes that ultimately gathered along the valley of the Little Bighorn in 1876. Not that Donovan forgets the other side of the equation. He does, from time to time, reflect upon the atrocities committed in the name of land, greed, gold, and progress against the Sioux and Cheyenne from 1860 through Wounded Knee. The book is not completely devoid of such analysis. But the overall tenor of the book is devoted to a detailed inspection of the actions of Custer and his subalterns on the days before, during, and after the great battle. There are only bits and pieces; shards of historical reference to the other side of the conflict. In this way, my preference is for Connell’s earlier effort as a more complete, more literary, more balanced view of the story.

That having been said, Donovan’s writing is crisp and descriptive, his scholarship is exemplary, and in the end, his steady review of the aftermath of what happened to Captain Benteen, called the “Savior of the Seventh”, and Major Reno, often portrayed in film and print as a cowering shell of a man during the battle, is thorough and evenhanded. Not the best of all the many books on the subject but, for someone interested in history, particularly history involving the enigmatic boy general, Donovan’s effort is well worth reading.

4 stars out of 5.