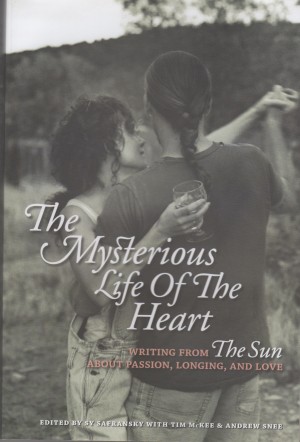

The Mysterious Life of the Heart edited by Sy Safransky, Tom McKee, and Andrew Snee (2009. The Sun. ISBN 978-0-917320-04-0

I’ve been a subscriber to Sy Safransky’s little experiment in literary journalism, The Sun, off and on now for almost twenty years. It is one of only two literary magazines that I subscribe to, Glimmer Train being the other. Modern Americans, it seems, don’t appreciate short fiction, or quality personal essays, or poetry to the same degree their readerly ancestors did. Remember when every major magazine, Look, Life, Saturday Evening Post, Ladies Home Journal, and the like contained a short story or two, a handful of poems? Well, most of those magazines are gone, and with their demise, short fiction, accessible and read by main street America has, to a large extent vanished as well. What remains are specialized literary magazines published by boutique presses, like Glimmer Train, or literary journals published by universities. The one exception to this generality is The Sun: Like it’s namesake, Sy Safransky’s bold little experiment in creative writing for the masses, a magazine that features personal essays, quality photography, thought provoking short fiction, modern poetry, and feature interviews with some of the most advanced and controversial thinkers of our day, burns bright and omnipotent. This collection is Sy’s attempt to pull fifty pieces of literature and poetry from the magazine’s extensive catalog of past work together to address a common theme: Love.

True to the vibe and heritage of The Sun, even the few essays or short stories in this collection that have a touch of humor to them contain sorrow and bittersweet reality. But that’s OK if you know in advance, before you crack open the book’s cover, what you’re in for. This collection is nothing if not consistent. Issue after issue, The Sun prints letters from its readers who are cancelling subscriptions because the writing in the magazine is “too dark, too depressing, too close to the bone.” Exactly. So are these stories, and, to a lesser extent, these poems. Take, for example, my favorite piece in the collection, “Red Flamingo Looks at Red Water” by Katherine Vaz, a tale of a forty-something mother, who, having lost her only child, a daughter, to a traffic accident that she witnessed, tries to reconcile her feelings for her husband (he was walking the girl across the street when the five year old slipped his hand and was hit by a vehicle) with her loss. Powerful and vibrant, the story held my interest not with voyeuristic morbidity but with the grace of its prose:

I don’t know how to rescue Henry from this. I would like to supplant the sensation of impact with sounds of sad beauty. At the music store, I find a CD of the Portuguese fado singer Misia. Fados are the traditional songs of fate, mournful; a singer risks disappearing into the heat of them. Misla has a Louise Brooks-style bob haircut and full lips ans is send to bring modern sensibility to this music of the past. Henry thanks me, inspects the CD, turns it over in his hand, sets it out of view, but does not play it.

Some folks who are pre-reading the manuscript of my latest novel, Sukulaiset: The Kindred (a novel of tragedy and turmoil set in WWII in Estonia and Finland) have made comments similar to those who write The Sun and either ask for their money back or state they are tired of tragedy and violence and loss to the point that they don’t want to read about it anymore. I understand this world weary view. But whether a piece of writing is one full of light and hope, or one based upon sorrow and loss, good writing is good writing. That’s what Safransky has cobbled together here: a collection containing more than enough heat and light to burn away the dark pall of heartache and loss.

4 stars out of 4.