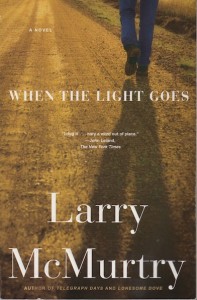

When the Light Goes by Larry McMurtry (2007. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-3427-3) brings back the Duane Moore character from The Last Picture Show (see my review below) and Duane’s Depressed (which I haven’t read). When last I knew, Duane was off to fight the Korean War mainly because he’d run out of options to make a living and better himself in Thalia, Texas: a dusty, dirty, windy spit of a town located not far from the Oklahoma-Texas border. Turns out that Duane has made millions in the oil industry after returning to Thalia, settling down, getting married and having four kids. His wife of many years, Karla, is dead and gone, the result of a car accident. Duane, after sixty-plus years of hard living, has heart problems; both romantic and physical. Turns out, despite his aging, decaying body, he’s still something of a catch: Both his forty-something bisexual psychiatrist and the seemingly coy California girl his eldest son has hired to work in the oil company office want Duane in bed. What to do? Duane has had a heart attack and must tread lightly when it comes to physical activity, including the horizontal bop.That’s pretty much what this book is from page 1 to 195. I’ll give the author this: It’s a quick read but that’s due to the brevity of the tale, not because it’s a page turner.

I’ve written similar reviews regarding books penned by other late-in-life male authors including John Irving and James Harrison. My chief objection to the more recent work of these writers is their irrational obsession with sex. Not story, not character, not setting; just sex. Now, I’m no prude. I’ve used sexual content and scenes in any number of my novels and short fiction. Not always, but when the story merits a romantic, sexual lilt, I have no problem writing scenes that involve disrobing and the act of procreation. That’s not what’s going on here folks: The fading light that McMurtry so desperately laments isn’t Duane Moore’s physical prowess or sexuality. It’s the disappearance, the vanishing of great characters and dialogue, both of which can be found in The Last Picture Show and Lonesome Dove. The story here is predictable and without purpose. We’re left to follow the aimless, pointless wanderings of an old guy trying to figure out which younger lass to bed. Duane’s attempts at self-reflection (like sex between strangers) seems empty and forced. McMurtry certainly could have written a protagonist who is without morals, without empathy, without direction, the sort of character who would fit the role of an indulgent, aging male far better than Duane Moore. But he didn’t take that risk. He didn’t ring that bell. The author, in a very real sense, played it safe and the result is an uninspired and unimaginative story.

In sum, I found very little to like about this story or its characters. I’d save the $14.00 cover price and buy one of James McMurtry’s CDs instead. James is the very gifted musical son of the author who writes fantastic Texas-inspired songs that feature lonesome lyrics and finely mastered guitar. Don’t get me wrong, Larry McMurtry remains a man who still commands my respect: His authorship of Lonesome Dove brought the oft-ridiculed genre of the Western into literary limelight. But the author who penned that tale, like the Duane Moore who inhabited Thalia at the time of The Last Picture Show isn’t to be found in the pages of When the Light Goes.

3 stars out of 5.