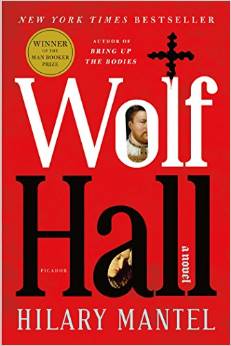

Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel (2009. Henry Holt and Co. Kindle version. ISBN 978-0312429980)

Let’s be honest. I will never write a book that makes it to No. 3 on the Amazon sales list. Hilary Mantel’s tome about the English politico and adviser (Thomas Cromwell) to Henry VIII during England’s split from the Vatican is there now and likely was No. 1 on the list at some point. That disclosure having been made, I am uncertain, other than the prurient interest such historical fiction engenders (what with all the beheadings and burnings-at-the-stake and rampant coupling), why the book is such a hit (it’s now a mini-series on PBS!). Not that the story, as gruesome and titillating as written, isn’t worthy of a read. It is. But, as other critics have noted, this series about Cromwell is more Mantel’s attempt, as a protestor against Roman Catholicism, to attack Thomas More’s (he of A Man for All Seasons fame) heroic legacy, a legacy that has left Cromwell, at least in popular fiction and the public eye, as a wretched, power hungry bundle of evil corruption, than to a retelling of the tragedies of Henry’s rule with objectivity. As with many historical figures of power, neither More nor Cromwell is all saint or all sinner, though Mantel’s attempt to soften the historic Cromwell is at least somewhat successful.

I found the author’s use of the third person subjective case (“He” instead of “Thomas” or “Cromwell”) throughout the tale an odd choice for the genre. Most historical fiction is written in the third person omniscient where the narrators are described by name, not pronoun. Not so in this work. It may seem a minor point but I found the author’s choice in this regard an odd one. In addition, the plot and action are confusing and difficult to follow, though the historic details are never in doubt, making this at times, a very difficult, though well described, tale to follow.

And, as I have said in past reviews of other novels that rely solely upon the basest of human experience to propel their plots forward (e.g., No Country for Old Men), a novel that completely avoids redemption and light for the sake of story, no matter how serious the subject matter, is half a story at best.

Still, like any witness to a train wreck (I knew what grisly ends awaited Sir Thomas, Queen Ann, and even the anti-hero, Mr. Cromwell but I kept on reading despite that insight) I had little difficulty finishing this book. It was not so badly written or constructed to the point where I stopped caring (the situation I find myself in having trudged through most of James Joyce’s Ulysses). Despite the above-noted critique, and some questions as to the author’s use of historical fiction as a platform to pontificate against the modern Roman Catholic Church, I will likely read the sequels. Even critics can’t avoid being curious when heads are about to be lopped off and maidens are being led to the stake…

Peace.

Mark

3 and 1/2 stars out of 5.