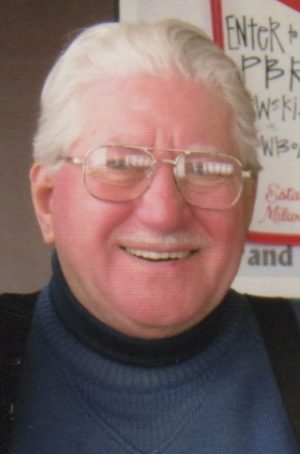

How do you capture the spirit of a man in words? I mean, a sculptor, a good sculptor, can do it in rock or wood, right? If you’ve seen any of Michelangelo’s work in marble, or Rodin’s The Thinker carved from stone, I think you’ll agree. The same is true of any painter worth his or her easel. The nuances of a person’s soul, their essence, can, if the artist is talented, be conveyed on canvas by replicating that one glance, that one smirk, that one wink everyone remembers. Music, the medium of Duke’s essence, might be a good choice for trying to figure the guy out but no one here, least of all Duke’s family and his fellow musicians want me to start trying to replicate Duane Tourville in song. So, as I struggle writing this piece, listening to jazz classics on Youtube—a real contradiction since Duane never owned a computer—“All of Me” playing softly in the background, I’m stuck trying to capture a beloved husband, brother, stepfather, grandfather, great grandfather, uncle, and friend in a eulogy. But here goes.

It’s not an easy thing to be a stepparent. Especially a stepparent to three Munger kids and their respective broods. Even though Duke entered into the picture when I was already married and a father and practicing law in Duluth, and Dave was already gainfully employed, and Annie was wrapping up high school, the point being, we weren’t little kids when Mom and Dad finally pulled the plug and Mom and Duke started spending time together, such transitions and change can be troublesome. Many such late-in-life partnerships fail. This one didn’t. From the very beginning, Duke was an engaged stepfather and grandfather despite never having kids of his own. And there’s absolutely no question he, in a word, simply adored Barbara. The two of them, though never perfect, were perfect for each other. How Mom found a railroad man who was elegant, dapper, talented, generous, thoughtful, and dedicated after both of them had been married to other folks, well, that really is a mystery. But a mystery that served them and our family well.

Most of you know that Duane had a lifelong love affair with another lady, a big blue one. Lake Superior was in Duke’s DNA likely because of his father, Ransom, who once operated an excursion boat on St. Louis Bay. In any event, it wasn’t long after Duke and Barb were married that my older boys, Matt and Dylan, were invited to experience the glory of Lake Superior. Matt, our eldest, remembers a trip from Grand Portage to Isle Royale in the company of Rene’, me, Barb, and Duke aboard the Ransom II not so much for the fun and excitement but for the fact that as we left Mark Rude and his mother at Fisherman’s Home and headed up the east coast of the island, the seas became rough. The two and a half to three foot swells and dark sky didn’t faze Captain Duke who invited me up on to the fly bridge to sip Bud as the little 26’ bluewater boat bounced through weather. Matt remembers Grandma Barb’s solution to my wife’s uneasiness in the cabin below us was pretty straightforward: Brandy and seven. Lots of them, allowing us to circumnavigated the island without incident. A few years later, Matt joined Grandma and Grandpa on the Ransom II for an even longer voyage, a trip to the Keweenaw. Again, Captain Duke was a master of his boat and respected the big lake enough to know when to stay in port and when to venture out.

Dylan, my second son, recalls a week-long trip from Barker’s Island to the Apostles on which he caught his first lake trout. On a shorter trip, Grandpa let the eight year old captain the boat from the fly bridge but made a serious miscalculation: Dylan had chowed down a bag of Doritos that ended up being hurled over the boat’s side as chum.

Chris and Jack, our youngest sons, never got to experience personal voyages with Grandpa on the Ransom II. By the time they came along, Duke and Barb had sold their place in Superior and traded in the Bertram for a pontoon boat. But you know Duke. The pontoon boat he bought wasn’t just a 20 footer with a cheap Force outboard to be used for lazy tours of Island Lake where the Tourvilles built their new home. No, Duke invested in a twenty-six foot Tritoon powered by a 260hp inboard outboard, a boat capable of pulling three water skiers and reaching 40 mph. No sedate, putt-putt for Captain Duke! Both Chris and my brother Dave reminded me, when I asked for reflections of the Old Captain, of how Duke loved to tow his grandkids behind that pontoon, starting out slow, a can of Bud in hand, gradually opening the throttle. Duke believed it was his job to flip the kids off the tube and when he wasn’t able to do that, which was rare, he begrudgingly gave the rider a big “thumbs up.”

When Duke and Barb moved to West Duluth from Island Lake, the pontoon moved with them. They used the Tritoon to host Labor Day gatherings on the St. Louis River. If the weather was good, the tube came out. If not, we just took a ride. My sister Annie remembers one return trip where white caps tossed passengers around like ragdolls but had no affect on the man in charge. Despite the rough seas, Captain Tourville kept the boat on course, a grin on his face and a cold beer in his hand.

One Labor Day, we were returning to Boy Scout Landing on the pontoon when we passed a fishing boat anchored near shore. A woman was in the water next to the boat thrashing and screaming something about a dog. Duke sprang into action and raced to rescue the floundering woman. The family dog had apparently jumped overboard and was having a jolly good time paddling around the boat. According to her husband (who remained uncommonly calm) the woman had panicked because she thought their dog couldn’t swim, jumped in, and then remembered that she was the one who couldn’t swim. My brother Dave, brother-in-law David, and I opened the front gate on the pontoon and tried to pull the woman out of the water. But here’s the thing: That woman was as big as a house. When we yanked on her arms, we nearly pulled them out of their sockets. She was panicked and tearful and just about spent as Duke held his boat in place and we worked out the logistics. My brother dove in the river. David and I grabbed a beach towel and threaded it under the woman’s arms. It was shallow enough for my brother to stand on the bottom, put his hands inelegantly on the woman’s butt, and lift. With Dave underwater and pushing, and two of us pulling, we plopped the overly large woman onto the pontoon’s front deck. Duke’s response, as he threw the inboard outboard into reverse? He simply grinned, opened up the throttle, and brought the tearful woman back to Boy Scout Landing.

As his obituary said, if Duane wasn’t on water, he was on snow. Barb and Duke weren’t part of the original group that began the Ski Hut trips to Bridger Bowl but they soon became part of the crew. Fifteen years ago, when our youngest son Jack was five or six, Mom and Duke convinced Rene’ and I to join them. Jack learned to ski the right way, as Grandpa Duke would say: he learned in the mountains! Since then, all four of our sons and Annie’s family have made the trek to Bozeman at one time or another, experiences with family and friends that we’ll never forget.

Duke was an elegant and graceful skier who constantly challenged my boys and Annie’s two girls, Madeline and Emelia, to “race”, which, since there weren’t any gates set up, meant bombing the hill. Grandpa claims he never lost a race and I guess, we can’t really dispute his bragging at this point, can we? Chris remembers Grandpa Duke skiing a steeply pitched run and “buying the farm”, requiring Chris to stop and walk back up the hill to help a very snowy Grandpa dig out his skis and poles. Once, Duke and I were skiing Pierre’s Nob at Bridger when I led him down a back slope, a black diamond, not knowing that I was taking a seventy-five year old guy into a field of awful moguls and ice. We made it through but that was the last run Duke skied with Mark that day!

Though never a soccer or hockey player, Duke made sure he and Barb were there for many, many of his grandkids’ athletic contests. Even more important, he was there, working as a crew chief when my youngest son, Jack, organized his Eagle Scout project. Duane gave up the Saturday of Memorial Day weekend to be at Grace Lutheran Church leading a group of five or six scouts putting together benches as part of Jack’s project. The kids of Grace still use those benches when enjoying a campfire, the benches a lasting legacy to Grandpa Duke’s generosity with his time.

He never missed a gathering at my brother Dave’s house in South Range and he was proud of the lives that Diane’s daughters and Grandson Jonathan were living. The fact that Jonathan is now working the same rails that Grandpa Duane engineered on for over 45 years is something, I’m sure, that makes the old man’s chest puff out with pride.

Duane grew up in a large and loving family. Jack and Carol (two of his siblings) and their spouses were there every day of Duke’s last stay at St. Luke’s, constantly talking to him, trying to rally his spirits, praying, like all of us, for a miracle. The miracle never happened but oh, the stories his brother and sister told! There were tales of Duke and Jack ski jumping throughout the Midwest, tales of familial teasing, the typical sort of thing you’d expect. But the one tale that really stuck with me is one Jack told, and one I’d heard Duke himself relate. When the boys were on the cusp of being teenagers, around ten or eleven, and school was out for the summer, the Tourville boys hitch hiked to the farm of a family friend outside Ashland, Wisconsin. They were to work on the farm for the summer. It was left to the boys to figure out how to get from the West End to Ashland on their own. Different world, different time. Anyway, the way Jack tells the tale, the boys made it to Ashland by dark, having hitched numerous rides along US Highway 2. With no tent, no place to stay, the two pre-teens bedded down in the shrubs near the band shell in the city park only to have their sleep disturbed during the night. No, it wasn’t the cops or wildlife that woke Jack and Duke. The boys were startled out of sleep by the sounds of a man and a woman making love in the bushes just a few feet away from the giggling, hysterical boys. And you thought farm kids learned the birds and the bees in the barnyard!

Did you ever see Duane unhappy? Shelly, my daughter-in-law can’t recall seeing Duke without a smile beneath his pencil thin moustache. She calls it “the best smile ever!” And, like I said earlier, that smile wasn’t just reserved for folks he knew well. Lisa, my other daughter-in-law, the gal who gave Duane the nickname “Troublemaker” or “Trouble” for short, says that from the moment she first met Grandpa Duke, he was thoughtful, engaging, and welcoming. And his joy, his interest in folks extended to the little people in his life. As he awaited heart surgery at St. Luke’s, Duke talked to his great-grandson, Adrien, who stopped by to visit. If Duke was nervous about the impending triple-bypass and valve replacement, he didn’t let on. Which, if you know Duke, was not his usual demeanor. Hospitals and doctors tended to make him nervous and fretful. But not this time. No, he and Adrien, who, like his father Matt, knows many variations of the word “Why?” had a good give and take including a discussion of Grandpa ordering meatloaf for dinner, a meal that Adrien advised he’d had for lunch that day at preschool.

Most of you know that Duke was a man of faith. He loved this big old church, a church he came to late in life. Given that, I don’t want to be disrespectful when recalling the life of a guy who had five Episcopal priests, a deacon, an Evangelical preacher, and a Catholic priest visit him, anoint him, pray for him, and say the last rites over him when he was in St. Luke’s. But I don’t want to leave you with the impression that Duke was a perfect man who never got angry or said a cross word or made a mistake. Hell, he was married a couple of times before he got it right with Mom so there’s that to mull over. And, let’s be honest, there were times when Duke liked beer a bit too much. He could also, if you pushed the right button, show his temper. I know. I experienced it a time or two, as this last story will make clear.

When my mom and dad divorced, we’ll not go into the details here, let’s just say that my mom did all right in the settlement. After she and Duane got married, he sold his Spirit Mountain condo and the two of them planned and built a gorgeous house in Billings Park. I sort of wish they never left that place. Of the three homes they built in their 33 years of marriage, that’s the one I liked best. Hands down. Anyway. So Duane sold his condo and mom used her divorce settlement to build that lovely place on the water in Superior. I was still working as a lawyer, as a partner in my dad’s firm, at the time. One day my dad asked me about the new place Barb and Duke had built. News traveled quickly at the Paul Bunyan Bar. Without missing a beat, I said, “Well, Dad, it’s the nicest house you ever built.” Harry didn’t think that was funny. Word got back to Duke about what I’d said. And while I thought the quip was funny, the Frenchman didn’t. Duke wouldn’t talk to me for a couple of days after that.

Those of you who golfed and bowled or fished and boated or played music with Duane likely have hundreds, maybe thousands of similar stories of this gracious, kind, loving, joyful man. I urge you to come to the Kitch after the service, listen to some great jazz from his pals, and share your stories in a place that Duke loves. The old ski jumper, boat captain, and drummer will be listening in to make sure Billy Bernard plays all the right notes and that the bass and drums keep proper time. Trust me. Troublemaker wouldn’t miss a party.

As I end this reflection of Duane’s life, I’ll leave you with a poem I found online. Duke’s not here in person, but he’s here in spirit and he’ll be ever so grateful if, from time to time, you’d look in on his beloved Barbara. Stop in for coffee. Take her to lunch. Invite her to the ski hill to watch the grandkids and great grandkids bomb the hill. Call to chat. Send her a note. Drop off a good book. Duke will appreciate it.

The Sea Captain’s Wife

Often when I drink my tea

I dream of Duluth, by the sea

But though her hills are sweet and fair

It is the sea, which holds me there.

The jagged cliffs, remain as gifts

To me in my old age,

Where lilac heather and pines together

Traverse across the page.

Up the winding stair I go

Into the heavens grey,

And though it was so long ago

It seems but yesterday.

Still on the wind the autumn air

Comes in crisp and cold,

And buried with the gravestones bare

Are secrets left untold.

Beyond the walls of gabro stone

Lie ruins of the past.

I’ve come aways to be alone–

To make this moment last.

And when the boats come into shore

I take in all the bay,

For though I’ve opened an ancient door

I’m never far away.

Muse22 © 2015 (as adapted by MAM)

Thanks.