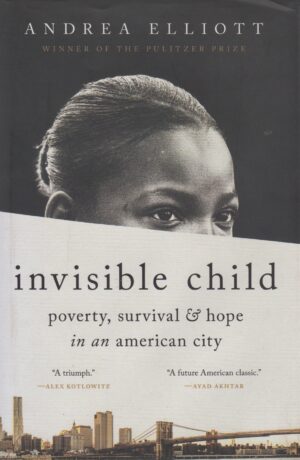

Invisible Child by Andrea Elliot (2021. Random House. ISBN 978-0-8129-8694-5)

Full disclosure: I worked in the area of child protection for the State of Minnesota as a District Court Judge. Every 8 weeks, I did child protection cases as part of my general judicial rotation, and over the 23 years I was active on the bench, I dealt with several thousand children caught up, for whatever reason, in Minnesota’s foster care, adoption, and termination of parental rights system. I have to say that my experience was nothing close to the judicial and legal system depicted in this book. The sheer volume of child protection cases, situations where social services becomes involved in protecting children who are in families impacted by poverty, abuse, drugs, alcohol, and/or poverty, in New York City boggles the mind. Yes, our child protection social workers in Minnesota, even in relatively staid and predominantly white NE MN, have heavy caseloads. But the number of families and children each social worker (and, for that matter, judge) is required to oversee in our child protection system is nowhere near as mind-numbing as depicted in this book.

Let’s digress. Elliott is a reporter with the New York Times who approached her editor with an idea: “Let me imbed with a family in the system and follow the children, the eldest, Dasani in particular, for not weeks or months but for years.” This the reporter does, chronicling the heart-wrenching story of Dasani from pre-teen to adult, from shelter to slum apartment to the Hershey School and back to New York City. She had unrestricted access to Dasani, the child’s parents, the child’s siblings, and even, through subterfuge, placements that would normally be off-limits to a reporter. Through a very objective and professional lens, Elliott describes the struggles of Dasani’s parents-both of whom who are chemically dependent, undereducated, and prone to violence-as well as their seven children regarding food, clothing, housing, employment, schooling, and safety. She pulls no punches and the depiction of Dasani’s successes, struggles, and ultimate acceptance that she cannot, even at a young age and with the positive assistance of teachers and other mentors, change her life or the outcome of her fate, is extremely unsettling.

In the end, this book offers no solutions to the fate of Dasani and the countless thousands, nay, millions of children who find themselves removed from the familial home by state social service agencies every year with an eye to protect those children from their parents, their lives, and their circumstances. But it’s a valuable reminder that parents and children caught up in the system are more than mere numbers and that, by and large, even the worst of parents (and Dasani’s parents have many, many failings) genuinely love their children and want them to succeed.

My only complaint with the book is that it’s horribly misprinted in that, inexplicably and unexpectedly, the story leapt from page 300 to page 413, confusing the hell out of this reader! The book then started anew with Chapter 40 (p. 443), only to flip back to page 317. What the author had to say from pages 301-317 is anyone’s guess! One would think Random House has better quality control than this … I know Cloquet River Press does.

In any event, this is a valuable read for anyone interested in the American social welfare system that deals with fractured, ruptured, and dysfunctional families.

4 stars out of 5

Peace

Mark