Interview with Stephen Kuusisto

Mark Munger is a writer, journalist, and retired judge who finds Finnish American folks fascinating. He recently interviewed New York Times acclaimed essayist and poet, Stephen Kuusisto.

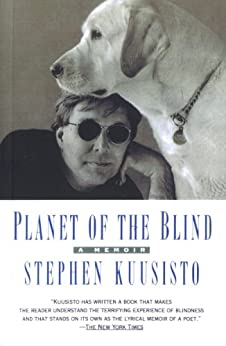

MM: A while back, I read The Planet of the Blind and wrote a very positive review of the book. Talk a bit about the process of writing memoir, about how one chooses what to leave in, what to take out.

SK: This is a great question. I have a practice of writing more than I need, largely as a way to get scenes on paper. Tom Wolfe once said that nonfiction is much like the novel in that it depends at the primary level on scene writing. So I write as many scenes as I can, then decide what needs to go. In Planet of the Blind I had a long parody of the old TV Guide magazine where I took American sitcoms and turned all the characters into blind people as a kind of schadenfreude exercise. It was funny but didn’t make the book because it got in the way of more impelling moments.

MM: Both in Planet and in a later memoir, Have Dog Will Travel, you reveal family confidences, including reflections about you mother’s struggles with alcohol and your own struggles with bullying and being born with significantly impaired vision. Has your mother read the memoirs?

SK: My mother read Planet of the Blind and was angry about it. Later she made peace with me by admitting the book was true. That took courage. She didn’t live to see Have Dog, Will Travel where I describe her violence. I was only able to be candid about that because my parents have passed away. It’s very difficult to write about trauma of any kind, whether it’s about sexual violence, bullying, drug and alcohol related distress, or the difficulties of being disabled or yes, a person of color. One often weeps while writing.

MM: Being a lifelong owner of Labrador retrievers, I think I’ve an inkling of what it’s like to partner with a dog. But your first guide dog, Corky, was obviously so much more than that.

SK: I’ve had four guide dogs all of them Labradors. They’ve been equally good at guide dog work—serious, reliable, entirely great, but they’ve all been different in temperament. Corky for instance loved chasing rabbits; my second dog Vidal ate things, many of them not so good. He once at a pair of gym socks! My third dog Nira was the half-sister of Corky and was noble and sweet. My current dog Caitlyn is the one who follows me from room to room because she wants to be with me every minute. They’ve all been soulful, empathetic, and wise.

MM: I found myself, in writing about my parents that with each draft, my critique softened. Did you experience anything similar as you edited your memoirs?

SK: It depends on my mood and the needs of the narrative. For instance, how do you explain not getting your act together about your disability until you’re in your thirties? That’s not easy unless you tell the story of being a child of alcoholics who put his energies into a dysfunctional family. I loved my parents and I’ve tried to be generous to them—remarking for instance that they had limited educations and support in the 50’s when I was small. They didn’t know how to manage disability except to pretend it wasn’t an issue. But they were also messed up and I absorbed abuse that’s not OK. You pick and choose what to say and how to say it depending on the requirements of the story, I think.

MM: Your father was an academic and the descendent of Finnish immigrants. I know you’ve visited Finland. What do you remember about those trips?

SK: I travel to Finland frequently. In some respects because Helsinki is the first city I remember, the place holds a special position in my imagination. I love the cobblestones, open air markets, the glorious parks, the Baltic in all seasons. As an adult I love the classical music scene, the theaters, opera, and of course the apocalyptic rock and roll.

MM: You are also an award winning poet. Is it easier or harder to write poetry than memoir?

SK: I can’t say whether one form of writing is easier than another. I tend to write quickly. My first drafts happen fast. Later I amend and edit. I tend to think poems (for me) come out of raw feelings—they can be tender or distressed—but prose is a bit more mediated by internal analyses. I’m not sure how to describe the difference.

MM: Being of extremely impaired vision, what’s your process like in terms of writing? What physical process do you employ to write?

SK: I used to write longhand with a pen and paper but I shifted to the computer. I just go into the cave of making (as Auden called it). I type and use screen reading software to read the pages back to me. For reasons I don’t understand I can’t dictate though the software for this is now exceptionally good.

MM: In your memoirs, you’ve discussed the importance of the Americans With Disabilities Act.

SK: I love the photo of Enrico Caruso guiding Helen Keller’s finger tips across his throat as he sings Samson’s aria about Samson losing his sight. Caruso was a peasant who grew up in poverty but, by the time of the photograph, he was as famous as Teddy Roosevelt. Helen Keller was also a public figure. There they are, having what a later generation might call a “Vulcan Mind Meld”. Whenever I think of this photo I want to be Helen’s fingertips. Imagine! Touching Caruso’s throat! Perhaps it’s an exaggeration to say that the ADA makes things like this more likely, but it’s not much of a stretch. Not long ago, I was permitted to spin the bicycle wheel that is part of Marcel Duchamp’s famous sculpture. That’s the ADA.

MM: I love this quote from Stephen King: “If you don’t have time to read, you don’t have time to write …” You must be a voracious reader.

SK: I read voluminously, mostly by downloading books on the Mac. I read poetry, fiction, history, nonfiction, memoirs and noir murder mysteries. I just read Oscar Wilde’s “de Profundis” which he wrote during and after his unjust and cruel imprisonment. It broke him. Yet it’s a deeply affirming book about the life of the mind and the soul. I also recommend “Dostoyevsky Reads Hegel in Siberia and Bursts into Tears” by LÁSZLÓ F. FÖLDÉNYI.

MM: My dream is to attend the Helsinki Book Festival and hawk my books to Finns. Any desire to attend the festival?

SK: I’ll go with you!

MM: You’ve written about the importance of the Kalevala to one’s understanding of Finnish history, culture, and literature.

SK: I talked to trees when I was six years old. There really were men inside those pines and I didn’t have to tell anyone. Years later, reading the Kalevala, I’d see I was a minor character in an ancient poem about wizardry. My job, the work of the inner life, is to never forget what the wizards have passed down. At the very least, I should distrust standard-issue transactional materialism. Even a simple pine tree is more interesting than is commonly supposed. The Kalevala is not for everybody but I know a Finnish banker who talks to a certain rock in the deep woods!

MM: What are you working on right now?

SK: I’m putting the final touches on a new book of poems. Here’s a poem from that book, due out later this summer:

Lamento (After Tomas Transtromer)

So much that can neither be written nor kept inside!

Such thin wrists; such brittle feelings.

I want to lie down behind the furnace

While outside springtime fusses with leaves.

I can add more—like how the weeks go by

And how the little kit of my heart beats

Or what avails from morning studies,

Two moths on a sill with messages.

I see how it is to not have much.I hear a winch groan in the next street.

What is this whistling, birds or wires?

I want this month to hurry.

I write things like: “weeks go by,”

“Apple trees have sorrows too,”

“Don’t lie about your writing…”

© 2021, Stephen Kuusisto