INTERVIEW WITH JOHN SIMON

MM:

Though you live in Helsinki, where were you born? Where did you grow up? What’s your ethnic/religious background?

JS: I was born in Richmond, Virginia in 1943 and grew up in typically suburban Pleasantville, New York, where I attended school (K-12). I was raised in a Reform Jewish home and congregation, but the community where I grew up was culturally mainstream Christian.

MM:

Fill the readers in regarding your educational path after high school.

JS: I entered Hamilton College in Clinton, N.Y. in 1961, spent my junior year at the Sorbonne in Paris, and graduated as an English major from Hamilton in 1965. The next two years were spent at Cambridge University, where I obtained a master’s degree before moving on in 1967 to the University of York, also in England, where I began a Ph.D. program focusing on the works of Samuel Beckett. My research included semesters in Paris, Rome, and Dublin. During 1967-70, however, I became deeply involved in anti-establishment politics and never defended my thesis.

MM:

Later, you found yourself living and working in Finland. Explain to our readers how that journey evolved. How did you acquire fluency in the Finnish language?

JS: In 1965-66, while at Cambridge, I played basketball and shared a flat with a Finnish student. We became close friends, but he returned to Helsinki to continue his studies at the Helsinki School of Economics at the end of the school year. During the summer of 1969, I traveled by car with two friends from York to Moscow. On the way, I stopped in Helsinki to spend a week with Kari. While there, I met my future wife, Hannele, who was also studying at the Helsinki School of Economics. In 1970, after spending time together in Paris, Copenhagen, and my family’s home in Pleasantville, we married in Helsinki and moved to New York, where I worked as director of a youth center in a politically active community organization on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Hannele taught in a daycare center run by the same organization. I later wrote about my work in New York and the challenges faced by young people of color at that time in To Become Somebody: Growing up Against the Grain of Society (Houghton Mifflin, 1982).

My work kept me on call 24/7. By 1982, Hannele and I had two children, Mikko and Elina. I wanted to spend more time with them while they were still young, so I took a sabbatical from my job, which we spent in a furnished apartment in Vantaa, Finland. The children and I began learning Finnish and getting to know Hannele’s relatives. I taught English (I was a certified high school English teacher in New York) and absorbed as much Finnish culture as I could in one year. As soon as we returned to New York, I began to feel that living in Manhattan imposed unfair restrictions on the children. They couldn’t walk out the door of our apartment without an adult to accompany them, whereas they had been able to ride bikes and wander around our Finnish neighborhood safely by themselves. Within a month, we decided to move back to Finland and did so in the summer of 1984. We’ve lived in Finland ever since.

MM:

At some point, you began work on the biography of the patriarch of the company you ended up working at in Finland. Can you explain how did that process come about and perhaps describe the process of writing a biography?

JS: I started working for KONE, one of the world’s leading elevator and escalator companies (best known in the Midwest for having acquired Montgomery Elevator in 1994) as soon as we arrived back in Finland. My job was to put together the company’s global in-house magazine.

KONE’s principal owner and CEO, Pekka Herlin, was a legendary business leader, having taken charge of a domestic company in 1964 and transformed it into Finland’s first truly multinational organization. He was brilliant but unpredictable; and like many of his Finnish contemporaries, he had a serious drinking problem.

By the time Pekka Herlin’s eldest son, the new CEO of the company, asked me to write his father’s biography, Pekka had been dead for several years. Many writers had asked the family for permission to write an authorized biography and gain access to his papers, but the family was afraid hi story might be sensationalized. In fact, the truth was sensational enough. I only agreed to write the book if I could do so honestly. If the family didn’t like what I wrote, they could refuse to publish it. I’d never written a biography, and the challenge was daunting. Pekka Herlin had five children, and they had been fighting among themselves ever since Pekka secretly transferred a controlling interest in KONE to his eldest son. I interviewed all of them as well as their mother and nearly one hundred others. I shared what I was writing with the family. Sometimes one sibling would tell me, “What X says is bullshit.” I would tell him or her, “I wasn’t there so I can’t say who is right. What I can do is write: ‘X says so-and-so. Y remembers it differently…’ and include both points of view.” In the end, a number of events beyond my control (a granddaughter was kidnapped and held for ransom; the youngest son published a blog on the eve of publication, saying his father was a monster) created an unprecedented amount of publicity, and KONE’s Prince became a bestseller with over 100,000 copies sold. It was written in English but translated into both Finnish and Chinese.

MM:

You are Jewish but living in a very secularized, Lutheran country. At some point, the uniqueness of that circumstance must have led you to explore the history of the Jewish faith in Finland, leading to another book which became Strangers in a Stranger Land.

JS: Helsinki’s only Jewish congregation is strictly orthodox and very conservative. I had no reason to connect with it during the first twenty-five years I lived in Finland. After KONE’s Prince was published, though, my editor read in one of the reviews that I was Jewish. He gave me a book to which he had contributed to which multiple authors dealt with ways in which the various Nordic Countries had been involved in the Holocaust. In the chapter on Finland, I saw a picture of a tent synagogue and a dozen or so Finnish Jewish soldiers on the Eastern Front, peacefully preparing for Sabbath services less than half a mile away from Germany’s 163rd Division’s headquarters. Then I saw pictures of two Finnish soldiers and a member of the women’s auxiliary, all of whom were awarded the Iron Cross by the German Army. I couldn’t believe my eyes! Then I read that although more than 200,00 German soldiers were stationed on Finnish soil during WWII, Finland was the only combatant country on either side that didn’t have a single Jewish citizen sent to concentration or death camps or harmed in any way by the Germans (23 Jewish soldiers in the Finnish Army did, however, die in battle, but they were killed by Soviet troops). I felt that I had to understand how such a situation – contrary to everything I understood about Nazi Germany and its treatment of Jews – could have come to pass. The best way to understand it was to write about it.

MM:

Strangers is a fascinating, very well-written, yet somewhat quirky book. It’s part historical novel, part straight history.

JS: I wanted people to learn about this unique situation. The number of readers willing to dive into a straightforward factual recitation of an out-of-the-way country’s history is relatively small. I felt from the outset that the predicament of Finnish Jews in a country with hundreds of thousands of German soldiers moving through it was inherently dramatic, and I wanted the reader to experience that tension. The only way to ensure that was to create characters with feelings the reader could recognize and identify with. On the other hand, so few people outside Finland know anything about the country and its history, let alone about its tiny Jewish population, that I had to provide a factual (but, hopefully, not too heavy) framework for the story. The result was a hybrid work that provides both the context and the drama in ways that augment each other.

MM:

Strangers was first published in Finland in Finnish?

JS: Strangers in a Stranger Land was short-listed for History Book of the Year during Finland’s Centennial Year, 2017. The head of the jury confided in me that the book might have won without the fictional content, which disqualified in the view of some of the jurors. I was initially worried about how the Finnish Jewish community would react to a foreigner’s “appropriation” of their history, but I received nothing but cooperation and support from community members. The nicest comment was made by a history teacher at Helsinki’s Jewish School, who told me: “You have colored in our history.”

MM:

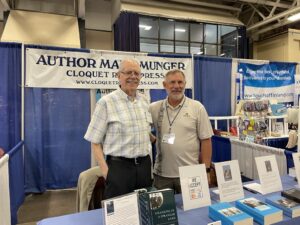

The book is also available in English. How did it end up here, available for purchase? Where can folks find a copy, other than on my website (www.cloquetriverpress.com : where I have a few copies you kindly left behind for me to sell).

JS: I had little trouble finding a Finnish publisher for the book but it was difficult finding an agent or publisher for Strangers in English, largely because Finland was not seen by them as a “commercially interesting” subject. Eventually, I was able to convince Hamilton Books to publish the (original) English version. The Finnish version is a large format hardcover with full-color illustrations; the English version is in paperback with black and white pictures, and I had to purchase a considerable number at the time of publication, which explains why I was in Duluth at FinnFest, selling books at your stand. The book can be purchased from Amazon or from Roman & Littlefield

( https://rowman.com/ISBN/9780761871491/Strangers-in-a-Stranger-Land-How-One-Countrys-Jews-Fought-an-Unwinnable-War-alongside-Nazi-Troops%E2%80%A6-and-Survived ) once the supply at Cloquet River Press is exhausted.

MM:

You did a fairly extensive book tour in the U.S with Strangers. Maybe give the readers a sense of when that took place and what the tour involved. Would you be available for Zoom presentations regarding the book if a Finnish American or Finnish Canadian group wanted to have you speak to its membership?

JS: In October-November 2019, I undertook an East Coast tour of libraries, community centers, bookstores, synagogues, Finnish-American societies, radio stations and museums that started in New York, wound its way to Northern Massachusetts, down through Boston to Rhode Island, Philadelphia, Washington D.C., Richmond, Roanoke and Atlanta. I ended up giving 40 talks in 40 days. Then in January-February of 2020, just before Covid would have made it impossible, I gave another twenty talks to various groups in Southern Florida.

Since then, I’ve given a few presentations via Zoom to groups in the U.S. and Israel. I remain willing to give remote talks to interested groups with the only reservation being that the 7-10-hour time difference makes it a bit challenging to schedule evening meetings in North America.

MM:

Are you working on another book?

JS: I’ve a new book coming out in Finnish translation in the spring. It tells about the experiences of a young Syrian boy growing up in the epicenter of the devastation of Damascus by the al-Assad regime and its Iranian and Russian allies. It accompanies him on his traumatic flight at 14 to Turkey (where he was mistreated) and Greece (where he almost drowned), until he was selected for relocation to Finland at the age of 16. He and I have grown close, and I have tried to support him as he tries to adapt to the very different customs and requirements of Finnish society at a time when the government is becoming increasingly hostile to immigrants from anywhere outside Europe and North America. Once again, I am having trouble finding a publisher for the English-language version.

MM:

It was a pleasure to appear with you at Finn Fest as co-panelists talking about our writing and our work regarding Finnish history. Stay well and keep writing!

JS: FinnFest was an interesting and rewarding experience, but the best part was gaining a new friend, who is not only an interesting and charming person but a wonderful writer. Thank you, Mark, for your books and your friendship.

(This article first appeared in the Finnish American Reporter, October 2023 )