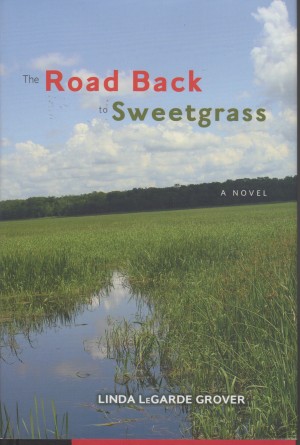

The Road Back to Sweetgrass by Linda LeGarde Grover (2014. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816692699)

Normally I’m up by 5:00am writing or managing my little press. This morning, images from Linda Grover’s latest novel bouncing around in my head like so many Indian legends and folk tales, I’m up at 4:00am. Way too early on a work day. But there it is. The power of great prose, or, as in the case of Grover’s previous book, The Dance Boots, and that of another Northland icon, Louis Jenkins, the power of poetry as prose, creates patterns and drumbeats whose echoes do not fade. The soft shuffle of deerskin against sand, the wind chattering through wild rice, the smell of frybread bubbling in lard, the angst of removal and betrayal, and the loss and the redemptive power of familial and romantic love are all here in this very slender novel centered around two endearing and universally appealing characters, Margie Robineau and Joseph (‘Zho’) Washington, and their able supporting cast. Written in a style and cadence that, for this waabishkiiwed (white man) replicates Native oral storytelling; sly and humor-filled, ironic and poignant, and non-linear as to time, in a manner that exchanges the first and third person without transition, excuse, or warning, Sweetgrass is a very different sort of prose from the equally powerful but much more straight forward style of Jim Northrup, another Ojibwe storyteller living in the Arrowhead Region of northeastern Minnesota. How well does Grover’s language translate from campfire to printed page? In this short excerpt, the author’s depiction of the sensuality exuded by Margie’s friend, Theresa, while cooking frybread, the reader is treated to a glimpse of Grover’s power as an elder relating an imagined familial history:

Theresa’s face was flushed and shiny with heat from the woodstove and from cooking; she had unbuttoned the top button of her blouse while she worked, and from the space between her breasts an almost invisible steam of Emeraude and perspiration mingled with the sweet Juicy Fruit scent of her breath and the warm, enticing scent of frybread to rise and float over the table.

As in many of Grover’s essays for the Budgeteer News, food and the preparation of meals play a major part in many of the scenes in Sweetgrass. Such snippets of ordinary human activity, tasks engaged in by all peoples, tie the exotic and foreign world of Native culture to experiences and situations non-Native readers can relate to. Attributes of the northern Minnesota landscape, the sights, the smells, the noises, the temperatures of outdoor activities such as snaring rabbits and ricing, buttress the authenticity of the ebb and flow of Grover’s non-linear narrative by inserting nature as a subdued yet omnipresent character in its own right.

Do not let the diminutive size of The Road Back to Sweetgrass lull you into a false assumption that this novel lacks the heft and weight to explore major cultural and historic issues. Within the confines of less than 200 pages, and without a heavy hand, Grover tackles; tribal allotments, casino gambling’s economic impact on tribal members, forced assimilation of Indian children into white culture, and the loss of Indian children to adoption. This last topic, one that plays out in the book as part of Dale Ann’s first person description of her rape and subsequent pregnancy, is a topic close to my own heart. For years, images of my brother David as a shaggy haired toddler standing on gray dirt in front of a ramshackle house in rural Becker County, have danced inside my head. I was only six years old when my parents adopted David, changing his name from David Paul to David John in honor of my maternal grandfather. As to what David’s Ojibwe name might have been, I have no clue because, over the intervening forty years, my parents insisted Dave was “Norwegian, 100 percent.” Turns out, he’s got a good quantum of Indian blood flowing in his veins. Turns out his father was a legendary Becker County Native American athlete. Reading Dale Ann’s account of her time spent “assimilating” through sexual predation and its aftermath made me wonder about the circumstances of my own brother’s conception, birth, and removal:

In signing I gave permission for the Indian Health Service to pay for the fallopian tubal ligation that had been done while I was still under anesthetic, which saved the county money, time, and the unpleasantness of dealing with a conscious young woman who might have regretted wishing that the baby that belonged to some happy mother was dead. Or, God forbid, have ever decided that she might wish to have another baby, a child of her own. Sometimes I had wished I had seen my baby, no, the baby who was never mine, just once. Later on I found out that some girls were allowed to do that, but I didn’t know to ask. I overheard one of the nurses telling another that there was a woman waiting for my baby on the condition it looked white. If I made her so happy, it must have looked white.

Despite tackling such weighty and difficult issues, the overall “feel” of the stories Grover shares with us leaves the reader believing in redemption, hope, and healing. My only criticism of this gem of a novel is that the ending makes us long to know what has become of Margie, the daughter, mother, and grandmother we love as one of our own by the end of the book. But I understand that this talented storyteller may be working on correcting that omission by gifting us yet again with her art.

5 stars out of 5.

Peace.

Mark