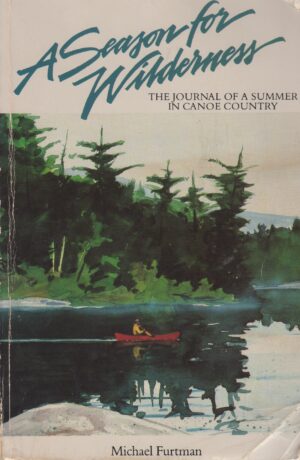

My pal Ken Hubert, a long-distance solo canoeist and adventurer, handed me this slender tome when René and I were at the home he shares with his wife, Vicky, in Faribault. Now, I have a stack of books in my “to read” pile on a credenza in my writing studio so I have to say, I wasn’t eager to add another book to the mountain of words awaiting my discovery. But because Mike Furtman is a FaceBook friend (whatever that means!) and writes such compelling posts, I ended up moving the book to the top of the heap. I’m very glad I did.

Furtman, his wife Mary Jo, and their Labrador, Gypsy were gifted, by stepping up as volunteer rangers for the U.S. Forest Service, a summer of working for no pay in the BWCA. They, like every other visitor to the Crooked Lake section of the wilderness, were required to do their work; maintaining designated campsites, replacing latrines, cleaning up messes left by discourteous campers, and the like; all from a paddled cedar strip and canvas canoe. No motors, no easy way to move from the legacy cabin they used as home base to patrol their assigned area, no mechanized tools or chain saws allowed in their arduous tasks. Their three month stay mirrors, in larger and expanded fashion, what most of us who’ve made trips into the BWCA (or its Canadian counterpart, the Quetico) experience: the first few days (or in the case of the Furtmans, weeks) involve getting accustomed to silence and listening and taking in the clear air and motor-less sounds of wilderness, which quickly, if you’re only in canoe country for a long weekend or so, turns to an easily accepted pattern of living, paddling, tenting, and eating that, in small ways, mimics the lives of the First People and the European Voyagers who called this place home or used its waterways as a transportation network.

Furtman’s writing is crisp and clear and, in not-so-disguised fashion, adopts and adapts the styles of other great outdoor writers, including Sig Olson, whose love of canoe country helped assist in its preservation. But unlike Olson and dreamier romantics, Furtman repeatedly cautions the reader that, in many ways, what we consider “wilderness” is only an illusion, a slight-of-hand of legislative protection that, with expanded visitation by well-meaning or unruly patrons, could easily be destroyed.

If you love good nature writing, pick up a used copy of this book. It is the perfect companion to a hot cup of coffee next to your summer fire pit.

4 and 1/2 stars out of 5.

Peace

Mark