Dinner at Bight with Charles Murto, Finland’s Ambassador to Canada.

You’ll need to enlarge the photo above to see everyone clearly. The picture was taken on Anni Stahle’s phone. Anni is the Head of Public Diplomacy for the Finnish Embassy to Canada. She’s the lovely lady in white. Across from Anni, in the vibrant red hair, is Sari Lietsala, Counsul, 2nd Secretary in the embassy. Next to Sari is my host and tour guide, Dr. Ron Harpelle, Chair of the History Department at Lakehead University. His wife Kelly Saxberg, a documentary filmmaker and Finnish Canadian (who invited me to speak at Finn Fest) is across the table from Ron. Next to her, and directly across from me (I’m wearing the green hula shirt) is Ritva Murto, the ambassador’s wife. Seated next to Ritva is Ambassador Charles Murto and to his right is Laura McSwiggan, Honorary Vice Consul in Ottawa. The last member of the group, seated to my right, is Margaret Wanlin-Hyer, Thunder Bay business consultant and wife of former MP (member of parliament), Bruce Hyer. There. Now you who I had dinner with at Thunder Bay’s trendiest restaurant on June 24th. Just how did I end up in such esteemed company you ask? Hold on a second and I’ll tell you.

It’s no secret that, as my second son Dylan once remarked, I’m (paraphrasing) “semi-famous in Canada.” Back in 2000, after my first novel, The Legacy was published, I took a chance. I was looking for places to promote my book: bookstores, civic groups, arts and crafts shows, and libraries were all targets of my less-than-sophisticated marketing strategy. Many times, emails and letters and promotional packets I sent out were ignored, discarded, or relegated to the slush pile. But when Barb Philp, head of Adult Services of the Thunder Bay Public Library system replied to my email and invited me to come up to Thunder Bay to read from The Legacy, I made the trip north on Highway 61 to Thunder Bay. Reading for the first time in front of a room full of strangers, I was mortified. Oh sure, I’d done a reading at my book launch at the Amazing Grace Bakery and another at the local Barnes and Noble store. But those events were held in my own backyard, attended by friends and family. I had no idea what awaited me in old Fort William that wintery night in 2000. Turns out, I had nothing to worry about.

In fact the experience at the Brodie Library compelled me to so something out of my comfort zone: I joined a writing group, the Northwestern Ontario Writers Workshop (NOWW). Through NOWW I participated in the annual book sale at the Waverly library, Finn Fling at Lakehead University, book signings at the local Chapters Bookstore, a conference at the Prince Arthur Hotel regarding Karelian Fever (the reverse migration of Finns from the US and Canada back to Soviet Karelia), the Sleeping Giant Writers Conference, readings at other branches of the Thunder Bay library, and a workshop discussing the perils and rewards of self-publishing. All this because one nice lady, Ms. Phelp, took the time to invite me up.

The tori (market) at Finn Fest 2016.

So here I am. It’s early Saturday morning. I’m at the Finnish Labour Temple on Bay Street. I’m crammed into a room with ten or so other vendors on the third floor of the building, selling my books to Finns attending Finn Fest. When I saw that the festival was scheduled for late June, I emailed Kelly Saxberg, who I’d met at a brunch following the debut of her film, Under the Red Star. That chance meeting, brought about because my novel, Suomalaiset: People of the Marsh, portrays the lives of Finns who settled around Lake Superior, propelled my work-in-progress, Sukulaiset: The Kindred (a story of Karelian fever) forward. 16 years after I first made my way north to Thunder Bay as an author, I find myself back in this lovely harbor city shadowed by mountains, talking to Canadians about Finns and hawking books to strangers.

Hall, Finnish Labour Temple, Thunder Bay.

My time here is limited. I have to leave the festival early to be in Two Harbors where I am slatted to deliver a eulogy at the funeral of my Uncle Wayne.

I arrived in Thunder Bay on Thursday evening. After settling into my room at the Prince Arthur Hotel, I strolled the town’s resurgent waterfront. I stopped to admire kids playing in a fountain, skaters doing tricks on concrete ramps, billowing sails of boats plying the bay inside the breakwater, and locals and tourists walking through the park on a beautiful summer evening. I found a pub, had a local brew, and set off to find something to eat. My favorite restaurant in town, Armando’s, closed. I wandered Port Arthur’s downtown until I found a pub serving food but I was disappointed to learn that the kitchen was closed, leaving a meat and cheese appetizer tray as my supper. I drank a Sleeping Giant lager, listened to two local boys emulating Neil Young, watched the crowd, and marveled at the lengthy journey I’d made in pursuit of fame.

On Friday, Ron Harpelle (Kelly’s husband) met me in the hotel lobby. We found a local haunt and over steaming cups of java, we talked politics, family, projects, films, and books for the better part of an hour. Ron was charged with meeting Ambassador Charles Murto and his wife Ritva at the airport. With time to kill, we piled into Ron’s van for an impromptu tour of the city. We visited Lakehead’s new law school and met the dean before heading to Chapters. I was bound and determined to buy a copy of Charlie Wilkins’s memoir, Circus at the Edge of the Earth. I’ve met Charlie, who came to Thunder Bay decades ago as the library’s writer in residence, a number of times, including at my first reading at the Brodie Library all those many years ago. He’s a well known essayist and writer with a national audience and a pretty neat guy. I own several of his books. I’ve always wanted to read Circus. Chapters is Canada’s equivalent to Barnes and Noble: a chain bookstore that believes bigger is better. Unfortunately, when I checked Chapters’ computer and the shelves, no Circus. In fact, no Charlie Wilkins whatsoever.

“We can order you a copy,” a helpful young female clerk suggested.

“I’m American,” I replied. “I don’t think that’ll work.”

I was buying a copy of Such a Long Journey by Canadian author, Rohinton Mistry just as Ron sauntered up.

“No Circus?” Ron asked.

“No Wilkins. Period.”

I paid for the book. We walked to the car.

“I really wanted that book,” I lamented.

My talk at the library went well. The audience listened intently as I explained researching and writing my two Finnish flavored books. Folks asked questions. I sold and signed books before making my way to the Labour Temple for the festival’s opening ceremony. I took a seat and watched an itinerary splash across the big screen in the crowded hall. Covers of my Finn books appeared. I smiled. Member of Parliament, Patty Hajdu, the Ambassador, and other dignitaries were introduced in English and Finnish. Several Finnish groups and musicians performed between brief speeches. And then, the festival was officially “open for business.”

Our dinner Friday night at Bight Restaurant was filled with political discussion, talk of the cultural differences between our nations, and consideration of just how The Donald was going to build a wall along the American/Canadian border.

“Is he going to float the thing in the middle of the Great Lakes?” I asked aloud. Given that Ambassador Murto, his wife, and staff were in attendance for casual dining, I’ll not repeat their responses here. Lets just say that the world is wondering just what the United States is thinking. Our meals were great. The wine was tasty. I avoided desert.

Saturday morning. I rose, packed, checked out, and drove the short distance to the Labour Temple for breakfast at Hoito (another of Charlie’s books, Breakfast at Hoito is one I have read and cherish). The restaurant in the basement of the old union hall wasn’t open. I walked across the street to Scandia and found the same Finnish pancakes I was craving. After eating and reading the Chronicle Journal, I set up my table in the tori (market) and waited for customers. Outside, the sky was darkening. Before long the clouds let loose, drenching vendors set up in the parking lot.

Storm brewing over the hall.

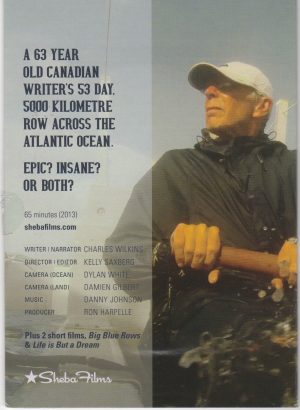

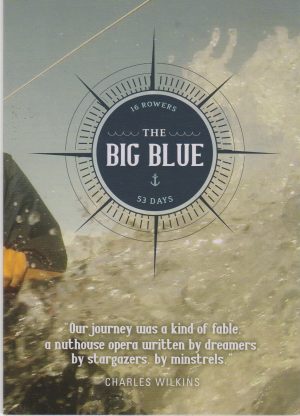

As I sit in my chair and watch Finns wander about, I consider the fact that I’ll likely outsell Thunder Bay’s most famous author because, inexplicably, the largest bookstore in town doesn’t carry his titles. Kelly arrives to say goodbye. She hands me a copy of The Big Blue, a documentary she directed about Wilkins and 15 other folks, mostly Canadians, who rowed from Africa to America. No sails. No motors. Just the power of their arms and legs propelling a catamaran across the Atlantic. I thank Kelly for her and Ron’s hospitality. Shortly after she leaves, I pack up and make my way back to the States.

I jet down Highway 61, and make my uncle’s funeral just in the nick of time. Later, after unpacking at home, I pop the DVD into the player. I watch and listen as my Canadian friend contemplates a journey that he, at 63 years old, seems ill equipped to make. And yet, despite the odds, he does what he sets out to do and then writes a book about the experience.

They aren’t even stocking his books in his adopted hometown’s biggest bookstore and yet, he soldiers on.

There’s a lesson in this tale for those of us who aspire to write something folks want to read.

Peace.

Mark

PS You can find copies of Charlie’s books (including his account of his Atlantic crossing, Little Ship of Fools) online if not on the shelves of your local bookstore!